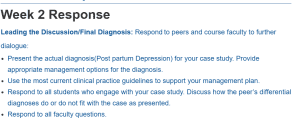

Week 2 Response

Leading the Discussion/Final Diagnosis: Respond to peers and course faculty to further dialogue:

- Present the actual diagnosis(Post partum Depression) for your case study. Provide appropriate management options for the diagnosis.

- Use the most current clinical practice guidelines to support your management plan.

- Respond to all students who engage with your case study. Discuss how the peer’s differential diagnoses do or do not fit with the case as presented.

- Respond to all faculty questions.

- See attached file ( Peer response)

- OK TO USE PAPER FROM ORDER # 57241, PLEASE DO NOT USE Myo clinic as reference

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Week 2 Response

Responding to Sarb’s Post

Hello Sarb,

This is an insightful analysis of the postpartum depression case study. Your systematic approach to differentiating between baby blues, postpartum psychosis, and postpartum depression demonstrates strong clinical reasoning skills. The emphasis on symptom duration as a key diagnostic factor is particularly astute. Indeed, the presentation in the patient is suggestive of baby blues, with features of sadness, insomnia, and changes in appetite. As you originally pointed out, the duration of symptoms is key; baby blues resolve within 1-2 weeks, whereas this patient was symptomatic for five weeks. This effectively rules out baby blues as a diagnosis.

Also, considering postpartum psychosis and then ruling it out demonstrates good clinical reasoning. Besides, the child’s lack of hallucinations, delusions, agitation, and generally odd behavior do not point to postpartum psychosis as a diagnosis. This is a much rarer and more serious condition than what we have before us here in this case. Lastly, your final diagnosis for postpartum depression agrees well with the case presentation. Symptoms include persistent sadness, tearfulness, fatigue, sleep disturbances, a difficult bonding process with the baby, feelings of guilt, loss of interest in activities, decreased appetite, weight loss, feelings of worthlessness, feelings of hopelessness, and inability to concentrate.

Building on your use of screening tools, it is worth noting that while the PHQ-9 is valuable, postpartum-specific tools like the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) are preferred in this context. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends these specialized tools for more accurate assessment in the postpartum population (ACOG, 2023). In clinical practice, I have found that combining the EPDS with a thorough clinical interview often provides the most comprehensive picture.

Regarding the DSM-5 criteria for postpartum depression onset, it is important to consider recent research suggesting a broader timeframe for symptom emergence. While the DSM-5 specifies onset within four weeks of delivery, many clinicians now recognize that symptoms can manifest later in the postpartum period (American Psychiatric Association, 2021). The American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation for screening at 1, 2, 4, and 6 months postpartum reflects this understanding. In my experience, adopting this extended screening approach has helped identify cases that might otherwise have been missed.

Your treatment recommendations of psychotherapy and antidepressants are spot-on. To elaborate, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) have shown particular efficacy for postpartum depression. A meta-analysis by the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) (2022) found that both CBT and IPT were more effective than other forms of psychotherapy for treating postpartum depression. For medication, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are indeed the first choice due to their safety profile during breastfeeding. Sertraline and paroxetine are often preferred due to minimal transfer to breast milk (Katzung et al., 2021).

Week 2 Response

The emphasis on social support is crucial. In addition to involving the husband and exploring paternity leave options, connecting patients with support groups can be tremendously beneficial. In my practice, I have seen remarkable improvements in patients who engage with both professional-led and peer support groups. Organizations like Postpartum Support International offer online support groups that can be especially helpful for mothers with limited mobility or childcare options.

Expanding on the treatment plan, addressing sleep deprivation is critical. There is a two-way relationship in which sleep disturbances create and worsen symptoms of postpartum depression. It may be improved by sleep hygiene strategies such as regularity in sleep times and avoiding screen time before going to bed. Sometimes, judicious use of sleep agents under medical supervision could be indicated. However, this needs to be weighed against the mother’s need to respond to the infant during night feeds.

Another important point to bring up is exercise during postpartum depression. A systematic review by Fotso et al. (2023) showed that physical activity interventions initiated in the postpartum period have a positive effect on reducing depressive symptoms. Such gentle exercises, like postpartum yoga, or even walking with the baby, may be recommended for physical and psychological improvement.

Nutrition also has a big role in postpartum recovery and mental health. This may be supported through the promotion of good nutrition with adequate omega-3 fatty acids, which have been associated with reduced risk of postpartum depression. Some studies have suggested that supplementation of omega-3 may have a positive effect on depressive symptoms; however, further research is needed in this area.

The final key element is the broader family context. A history of postpartum depression may influence the entire nuclear family, including the partner and other children. Facilitating resources and support to the partner, as well as the entire family, from the father’s support groups to appropriate explanations to older children, can facilitate holistic care.

References

ACOG. (2023). Screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. Www.acog.org. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2023/06/screening-and-diagnosis-of-mental-health-conditions-during-pregnancy-and-postpartum

American Psychiatric Association. (2021). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Booksmith Publishing LLC.

Fotso, M. N., Gonzalez, N. A., Sanivarapu, R. R., Osman, U., Kumar, A. L., Sadagopan, A., Mahmoud, A., Begg, M., Tarhuni, M., & Khan, S. (2023). Association of physical activity with the prevention and treatment of depression during the postpartum period: A narrative review. Curēus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.44453

Katzung, B. G., Kruidering-Hall, M., Tuan, R. L., Vanderah, T. W., & Trevor, A. J. (2021). Katzung & Trevor’s pharmacology examination and board review (13th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional.

Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). (2022, December 19). Psychological treatment for postpartum depression. NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK588870/#:~:text=In%20the%20National%20Board%20of