Psychological Reasons Behind Depression

Depression is among the most prevalent mental disorders worldwide. It affects people from all groups, ages, and economic classes. According to the World Health Organization, it is characterized by chronic sadness, a lack of interest in everyday activities, and a number of cognitive and physical symptoms, which affect over 280 million people from all over the world. Its effects are not confined to the individual level but enter into the sphere of families, workplaces, and societies, generally leading to disability and lesser quality of life. Undoubtedly, the very nature of depression is complicated; hence, laying down effective understanding and treatment is hardly expected, which, therefore, calls for the need to investigate its roots. Whereas the biological underpinnings include genetics and neurochemical imbalances that may contribute to the development of depression, psychological factors are important in understanding how personal experiences, thought processes, and social interactions contribute to the condition. Identifying the psychological causes of depression enriches one’s understanding of the disorder by underlining how cognitive patterns, emotional conflicts, and interpersonal dynamics present variability in individual experiences with depression (Chand & Arif, 2023). This forms the bedrock for therapeutic interventions at processive mechanisms of the mind, wherein personalized and targeted interventions can be carried out. This paper reviews major theoretical frameworks and examines the psychological reasons for depression, including cognitive, psychodynamic, behavioral, and interpersonal theories. From this review, insight could be gleaned regarding subjective facilitators of depressive symptoms and the maintenance effects. It is with these varied psychological explanations that the paper aims to illustrate more comprehensively how depression comes about and builds up, thus supporting the building of more effective and empathetic modes of treatment.

Historical Perspectives on Depression

Depression, previously viewed by ancient people as a form of divine or religious punishment, has been interpreted throughout many centuries for what it is: a complex mental health disorder. Ancient explanations of depression, then termed “melancholia,” were often put in terms of spiritual or moral failures. One of the first to consider melancholia a disease was the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, who proposed the disorder was the result of an imbalance of bodily fluids-or “humors”-particularly black bile. This theory remained influential for centuries and framed mental health within a medical and philosophical context. However, religious interpretations again prevailed during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and depression was explained as a form of punishment or as the result of demonic mediation (Kendler, 2020). Patients with signs of despair and withdrawal received religious treatment, exorcisms, or confession. This reflected the common belief during this time that mental illness was actually a moral failing rather than a medical concern.

Major Psychological Theories Explaining Depression

Cognitive Theory of Depression

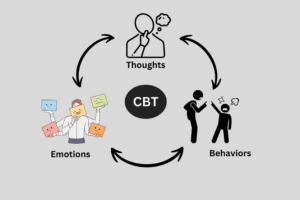

Aaron Beck’s Cognitive Theory of Depression represents one foundational framework in the understanding of depression from a psychological perspective. According to Beck, a depressed individual typically evidences a thinking pattern that is essentially negative and which moulds one’s thoughts concerning self, environment, and future. This distorted thinking pattern, one that has come to be called the cognitive triad, represents the essence of the theory: a negative view of the self, a negative interpretation of the world, and a pessimistic view of the future. Often reinforcing in a cycle, this triad tends to entrench the negative beliefs of worthlessness, hopelessness, and helplessness that are core symptoms of depression. Regarding Beck’s theory, the core contains cognitive distortions and distorts a person’s perception of reality; the person forms automatic negative thoughts reinforcing depressive moods (Chand et al., 2023). Classic cognitive distortions appearing in depression are all-or-nothing thinking, overgeneralization, and catastrophizing. A person may consider a minor setback in anything as proof of complete failure or think that this is a pattern because one unfortunate thing has happened. These cognitions are automatic and unwilled, often unconsciously experienced, serving to make the individual more vulnerable to depressive symptoms.

In the cognitive model, this kind of deformed thinking is seen as developing over time, which often originates in early experiences that reinforce negative beliefs about oneself and the world. Beck postulated that depressives may have a vulnerability to processing experiences through a negative filter, which interacts with life stress to activate the depressive symptoms.

Psychodynamic Theory

The psychodynamic theory of depression by Sigmund Freud is inclined to how unconscious conflicts, repressed emotions, and very early experiences can interfere with mental health. Freud viewed depression as a response to loss: it can also be developed through the unconscious internalization of hostile feelings, which he referred to as melancholia. Freud believed that unresolved grief or even the perception of loss can cause Individuals to direct their anger and sadness at themselves as an unconscious way of blaming themselves for the loss. Such internalized self-blaming feelings are manifested in the forms of guilt, self-criticism, and, eventually, depressive symptoms. Also, in Freud’s model, depression is linked to early childhood experiences, especially in regard to attachment and dependency. He postulated that given the losses, abandonment, or conflicts in childhood; the individual may carry these unresolved feelings into later years (Opland & Torrico, 2024). According to him, these events in early life create vulnerability to depressive reactions when the individual faces similar losses or challenges in their later life. One example could be the little child who feels abandoned in his childhood and develops a fear of loss deep inside him, hence always reacting more strongly to feelings of rejection or failure at a much older age.

Freud’s ideas served as the basis behind psychodynamic therapy, which helps uncover repressed emotions and unresolved conflicts so they can be processed by the individual in order to have a healthier emotional response. Contemporary psychodynamic theories focus on relational dynamics, viewing depression as a result of the interpersonal patterns a person learns early in their life. There is fair evidence that psychodynamic therapy, specifically long-term psychodynamic treatment, is effective in treating depression by helping patients understand underlying emotional conflicts and difficulties in attachment (Opland & Torrico, 2024). While the psychodynamic approach may be less widely used compared to CBT, it is still a useful tool in uncovering the deep-seated psychological roots of depression, especially in those with complex or recurrent depressive episodes.

Behavioral Theory

The behavioral theory of depression posits such environmental influences and reinforcement contingencies to be the sources of depressive symptoms. More particularly, Seligman’s theory emerged from experiments where animals exposed to uncontrollable, noxious events eventually ceased trying to escape even when escape was possible. This response called learned helplessness, has been generalized to account for human depression as a reaction to perceived powerlessness and repeated failure. Learned helplessness in humans is the nonmotivational effect wherein exposure to chronic adversity or recurrent failures cultivated feelings of helplessness and lack of control (Klonoff, 2019). For example, a person hurt at work or in personal relationships will soon start to feel that their effort is useless. Such beliefs that one is futile in influencing events advance passivity and resignation. These are the constituents of inactivity and low motivation characteristic of depression.

The behavioral model also indicates that a lack of positive reinforcement is another avenue to depressive symptoms. People who get little reward and gratification from their daily activities start refusing to engage in those activities any more, hence further reducing the possibility of encountering positive reinforcement. This cycle of withdrawal and lack of reward strengthens depressive feelings, moving individuals along a downward spiral into inactivity and despair (Klonoff, 2019). One such therapy, behavioral activation, flows from this theory in its attempt to increase the frequency of rewarding activities to challenge learned helplessness. By encouraging patients to gradually reintroduce pleasurable activities into their routines, this approach helps break the cycle of helplessness and supports recovery from depression.

Interpersonal Theory

Interpersonal theory describes the view emanating from attachment theory that most times, depression occurs as a consequence of problems in social relationships and attachment. Chinvararak et al. (2021) indicated that insecure or anxious attachment styles could underlie the vulnerability to Major Depressive Disorder-person’s dependency on others’ self-esteem and the vulnerability to perceived rejection. It assumes that depression could be the outcome of an interpersonal dispute: a misunderstanding, an unresolved argument, or prolonged social isolation, which results in feelings of worthlessness and lonesomeness.

These insecure attachments, which usually happen in childhood, go on to dictate interactions throughout life between a person and others. People with anxious attachment styles are too dependent on others for one’s approval and validation, and any disturbance in the relationships leads to great emotional shocks. Moreover, attaching avoidance will lead individuals to fail to connect with others, thereby making them isolated and unsupported socially, which again provides a way for depressive symptoms (Chinvararak et al., 2021). This theory underlines how healthy relationships are very important in order for the mental state to stay in good condition and underlines how dysfunctional interpersonal may lead to depression.

These relational problems became the reason for the development of Interpersonal Therapy, which would help people enhance their communication skills and deal with conflicts. The interpersonal model is based on the idea that alleviation of the interpersonal problem will decrease depressive symptoms while enhancing the social support network. This also serves to establish that IPT is effective in the treatment of depression, especially in cases where social factors are predominant (Kumar et al., 2022). By helping the individual understand their attachment style and improve their relationships, IPT offers a therapeutic approach toward treating the interpersonal roots of depression.

Cultural and Socio-Psychological Factors

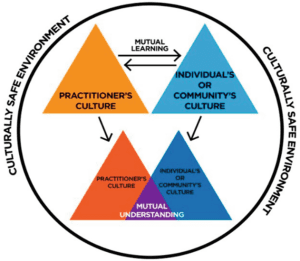

Depression is a condition characterized by cultural norms, stigma, and social expectations. Most societies tend to stigmatize depression and other mental health conditions as a moral failing or a weakness rather than a health problem. Because of this stigma, many people battle with their inner issues in private, which may keep them from talking to others about them and preventing them from getting therapy or assistance. Individual denial and minimization of their symptoms in settings where mental illness is highly stigmatized contribute to increased loneliness and, thus, worsened depression. Social expectations and cultural values concerning success, family roles, and personal responsibility finally give shape to depressive experiences. Being exemplary, in many collectivist’ cultural settings, family unity and interdependence would emphasize the responsibility to meet familial or community expectations (National Library of Medicine, 2021). Such failures can bring about feelings of shame and guilt, especially when one views him or herself as disappointing others. Individualistic cultures, in contrast, emphasize achievement and independence, and the self is often equated with success.

Moreover, cultural norms influence the expression of major depression. In some Asian and African cultures, depression may be manifested as somatic symptoms of fatigue and physical pain without overt expressions of sadness. Such variability affects diagnosis and treatment, since culturally interpreted symptoms may miss the signs for the psychic distress (National Library of Medicine, 2021). Understanding the socioeconomic context is important for the effectiveness of mental health interventions, enabling healthcare providers to approach depression with cultural sensitivity. From this perspective, using one’s cultural background can help an individual being treated by taking into respect various manifestations of depression and providing better support that takes into consideration special cultural values and challenges.

Treatment and Management Approaches

Treatment and management of depression are complex and require an approach that can allow for the consideration of the psychological causes of the disorder. Current psychological treatments, such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Interpersonal Therapy, importantly help individuals learn to identify and change maladaptive factors that influence depression, including distorted thinking, unresolved emotions, and interpersonal problems. These therapies provide systems through which cognitive, emotional, and social features of depression can be directly dealt with.

CBT, based on the cognitive theory, is one of the evidence-based approaches to treating depression. It specifically emphasizes the identification and challenging of cognitive distortions, which commonly maintain or foster depressive symptoms, such as catastrophic thinking, overgeneralization, and all-or-nothing reasoning. CBT scrambles cycles of negative self-beliefs by changing negative thoughts to more balanced and realistic ones (Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, 2022). It also utilizes behavioral activation through CBT by encouraging enjoyable activities in order to build positive behavior contingencies. Research indicates that CBT decreases depressive symptoms, and the downward-sloping relapse rates occur because of the accruing coping skills that create resilience.

IPT addresses the social aspects of depression, which can be overlooked so easily. IPT is based on the premise that depression may worsen as a result of poor interpersonal relationships, social isolation, or conflict. In IPT, patients work on communication analysis, social role disputes, and the development of social support (Bright et al., 2020). By diminishing interpersonal stressors, IPT not only reduces depressive symptoms but also enhances social support mechanisms that may be important in preventing future episodes. Of all treatments, the IPT seems to work most effectively for patients whose development of depression is closely related to a life transition, a relationship problem, or some social conflict.

Beyond these structured therapies, a holistic approach to treating depression has gained recognition; it brings into view the need for an integrated model incorporating psychological, physical, and lifestyle interventions. For example, more attention has been paid to physical exercises, meditation, and nutrition that support mental health, enhance neurotransmitters regulating mood, lessen feelings of stress, and lead to general well-being. In addition, holistic approaches often include psychoeducation. Patients are informed to have a better understanding of their condition in order for them to be in a position to take initiative in their recovery process. Holistic depression treatment plans offer a wider perspective, considering the unique psychobiological and social contexts of each failing patient (Chand & Arif, 2023). An integrative model based on such recognition that depression is often a multifactorial disease, best treated by combined therapies targeted at the mind, body, and lifestyle, makes it possible for health caregivers to make longer and more personalized treatment plans, proliferating the sufferer’s capability of self-managing depression and improving quality of life accordingly.

Conclusively, the psychological explanations of depression give insight into the qualification of the condition and reinforce the fact that it cannot be approached from one perspective. Such perceptions about the development of depressive experiences allow mental health professionals to find nuances that justify a variety of therapeutic approaches. Each of the diverse psychological theories, cognitive, psychodynamic, behavioural, and interpersonal, unveils one more face of depression, and all are called upon in the effort to deal with mental illness from a multi-model perspective that reflects the richness of depressive disorders. As psychology advances, there should hopefully be a better implementation of such theories in more holistic and personalized treatments to help improve outcomes in patients with depression. Interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic approaches, and interpersonal therapy will all be enhanced, the more this treatment can be tailored to a person’s psychological background, making it complete and holistic support system against the needs of each. Additional factors may be exposed, by future psychological research that influences depression in various ways, including culture, electronic technology, and other such pressures exerted by contemporary civilization, which may shape mental life. In this way, by expanding the purview of psychological inquiry to include such emerging influences, we can devise interventions that are more effective and sensitive. Eventually, such gains will contribute to lowering the global burden of depression, thereby playing a positive part not only in improving the quality of life for those who suffer but also in enhancing tolerance for and acceptance of mental health issues in general.

References

Bright, K. S., Charrois, E. M., Mughal, M. K., Wajid, A., McNeil, D., Stuart, S., Hayden, K. A., & Kingston, D. (2020). Interpersonal Psychotherapy to Reduce Psychological Distress in Perinatal Women: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228421

Chand, S. P., Kuckel, D. P., & Huecker, M. R. (2023, May 23). Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT). National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470241/

Chand, S., & Arif, H. (2023). Depression. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430847/

Chinvararak, C., Kirdchok, P., & Lueboonthavatchai, P. (2021). The association between attachment pattern and depression severity in Thai depressed patients. PLOS ONE, 16(8), e0255995. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255995

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. (2022). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279297/

Kendler, K. S. (2020). The Origin of Our Modern Concept of Depression—The History of Melancholia From 1780-1880. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(8). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4709

Klonoff, D. C. (2019). Behavioral Theory: The Missing Ingredient for Digital Health Tools to Change Behavior and Increase Adherence. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 13(2), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932296818820303

Kumar, M., Yator, O., Nyongesa, V., Kagoya, M., Mwaniga, S., Kathono, J., Gitonga, I., Grote, N., Verdeli, H., Huang, K. Y., McKay, M., & Swartz, H. A. (2022). Interpersonal Psychotherapy’s problem areas as an organizing framework to understand depression and sexual and reproductive health needs of Kenyan pregnant and parenting adolescents: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05193-x

National Library of Medicine. (2021, August). Culture Counts: The Influence of Culture and Society on Mental Health. National Library of Medicine; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44249/

Opland, C., & Torrico, T. J. (2024). Psychodynamic Therapy. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606117/

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Term Paper on what are the psychological reasons behind depression?

Final papers should be 8-10 typed, double-spaced pages (page count does not include references or cover page) and are due by the date and time listed in schedule (2 points will be deducted for each day the paper is late). Papers should be in APA Style Format. Please refer to the Purdue Owl for additional guidance on APA Style at :

Psychological Reasons Behind Depression

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/01/.

Your course paper will be graded primarily on the basis of creativity and critical thinking, but variety and style will also be considered. To prevent carelessness, spell-check your paper and proofread the printed version for typos.