Neurocognitive Case Study – Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

The case presented is of a 75-year-old widowed Caucasian male presenting with complaints of forgetfulness, difficulty completing familiar tasks, and recent episodes of getting lost while driving in familiar areas. Reportedly, the symptoms began two years ago. The suspected neurocognitive disorder is a major neurocognitive disorder due to possible Alzheimer’s disease (AD), without behavioral disturbances, mild.

Alzheimer’s disease is an insidious deteriorating neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by significant impairments in the cognitive functioning and behavior of an individual. These functional impairments include language, memory, reasoning, comprehension, and judgment. The manifestations of AD vary with the stage. Episodic short-term memory impairment is an early and the most common disease symptom. As the disease progresses, language impairment and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as agitation, social withdrawal, psychosis, depression, and wandering also appear. Dyspraxia, sleep disturbances, incontinence, and extrapyramidal side effects such as dystonia characterize late-stage AD (Breijyeh & Karaman, 2020).

Neuroanatomy of AD

The pathophysiological principles underlining AD development are the loss of neurons in the neocortex and the basal forebrain (Breijyeh & Karaman, 2020). In healthy individuals, the amyloid precursor proteins are split by secretase enzymes to form tiny, safe neuronal fragments. In the pathogenesis of AD, sequential cleavage of the amyloid precursor proteins by the beta and then gamma secretases result in abnormal beta amyloid proteins. Accumulation of the beta-amyloid proteins in specific regions of the brain involved in memory functionalities causes neuronal toxicity with consequent manifestations of AD symptoms. As the levels of the abnormal beta-amyloid proteins approach the tipping point, aggregation of fibrillary amyloid proteins is favored over normal amyloid, causing disease progression (Breijyeh & Karaman, 2020).

Physiological and Mental Status Exam Findings in AD

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. The physiological and mental status exam findings often correspond with the stage of the disorder. Each stage of the disorder can last for several years. In the early stage, memory loss is the predominant manifestation, and patients at this stage usually present with diminished short-term memory with intact long-term memory. The mental status exam will also reveal impairment of organizational skills. Loss of instrumental activities of daily living may also be apparent in the early stage (Abubakar et al., 2022).

As the disease progresses, language disorders and impairments in visuospatial skills appear. Neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy, disinhibition, psychosis, and social withdrawal begin to manifest in the later stages of the disease. Physiological findings in these later stages include loss of language, difficulty locating items, poor navigation and subsequent wandering, and poor conceptualization of distance. In the late phase of the disease, dyspraxia, loss of primitive reflexes, extrapyramidal side effects, olfactory dysfunction, and sleep disturbances appear. Physiological findings in patients with end-stage AD include sleep disturbances, incontinence, difficulty performing learned motor tasks, dystonia, akathisia, and anosmia. Mental status exam reveals memory loss, unresponsiveness, poor orientation, poor judgment and problem-solving, and speech impairments (Abubakar et al., 2022).

Cultural, Spiritual, and Biopsychosocial Factors to Consider for AD

Race, culture, spirituality, and biopsychosocial factors should be taken into consideration when diagnosing and managing AD. AD is an insidious progressive neurocognitive disorder. One cultural consideration to make is the perception of the disease across cultures. Rosselli et al. (2022) note that some cultures view AD as a normal part of aging and may not give it the medical considerations it requires. Likewise, stigma is another challenge when managing this disorder. Lack of awareness of AD, coupled with shame and guilt about the disease and other mental health conditions, may impact treatment. Spirituality is essential in the management of AD. In the later stages of the disease, it has been noted that prayer and meditation help preserve a sense of meaning and hope among patients with AD. A biopsychosocial factor to consider in AD is the role of the family in managing the disease. Family is an essential aspect of well-being that inspires hope in patients with AD. Caregivers must encourage and allow the patient’s loved ones to participate in and be a part of their care.

Diagnostic Testing

A probable or possible AD diagnosis is arrived at after a comprehensive subjective, physical, and mental status examination. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Health Disorders (DSM) outlines the diagnostic criteria for AD. As per these criteria, a positive diagnosis of AD is made in the presence of a decline in cognition, memory, and learning that interferes with independence in completing instrumental activities and activities of daily living (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Screening tools such as the Mini-mental status examination (MMSE), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Exam (MOCA), the Mini-Cog Examination, and the SLUMS assessment have been deemed effective in determining cognitive decline. These screening tools can aid in diagnosing mild and major neurocognitive disorders. According to Boland et al. (2022), individuals presenting with symptoms of AD should receive a laboratory workup to rule out things such as infections and vitamin deficiencies that may be causing cognitive impairment. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography scans (CT) can help identify brain structure abnormalities.

Diagnosis

Primary Diagnosis

The presumptive diagnosis is a major neurocognitive disorder due to possible Alzheimer’s disease (AD) without behavioral disturbances, mild (G30.9, F02.80). AD is characterized by functional and cognitive decline. Persons with the disorder will commonly manifest with memory loss, impaired learning, difficulty recalling events, increased reliance on task organizers, and repeating themselves in conversations (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

The patient in the case study presents with short-term memory loss, difficulty completing familiar tasks, and getting lost while driving in familiar places. Assessment findings revealed that he was only oriented to person and place. He was noted to be confused regarding the date and time. His concentration was impaired, and he was unable to complete calculations. The patient had slow thought processes, repeated himself during conversations, struggled to find words, had difficulty in activities of daily living such as driving and cooking, and needed reminders for medications. He meets the DSM-5 diagnostic criterion for evidence of a notable decline in cognitive functioning from baseline and cognitive impairments interfering with daily functioning. These manifestations are consistent with those of early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, warranting the above diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Major Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Possible Lewy Body Disease, Mild (G31.83, F02.80)

Lewy Body disease (LBD) is also known as dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). DLB is a progressive neurocognitive disorder characterized by a decline in cognition, decline in intellectual functioning, psychotic symptoms, movement disorder, and sleep disturbances (Prasad et al., 2023). The neuroanatomy of Lewy body disease reveals acetylcholine deficiency in the substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, and dorsal raphe (Menšíková et al., 2022).

Physiological findings in the disease include loss in executive functioning, muscle rigidity, tremors, sleep disturbance, and bradykinesia. Memory loss is apparent in the later stages of the disease (Menšíková et al., 2022). Psychiatric findings include hallucinations and delusions. Poor perception and subsequent stigma are a cultural consideration for the disorder. Prayer and meditation are likely spiritual considerations for the disorders, as patients tend to find hope from spirituality during the later stages of the disease. Family is a biopsychosocial consideration for DLB, as the family is a source of psychosocial support for patients diagnosed with the disorder. LBD is a progressive disorder with a fair to poor prognosis. The average life expectancy of individuals with the disorder is five to eight years after diagnosis (Haider et al., 2023).

Major Neurocognitive Disorder Due to Possible Frontotemporal Degeneration Without Behavioral Disturbance, Mild (G31.09, F02.80)

Major frontotemporal neurocognitive disorder is another possible differential diagnosis for this patient. A loss of intellectual functioning characterizes this disorder. Neuroanatomical analysis reveals that the disease affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain and results from the deposition of abnormal protein aggregates (Antonioni et al., 2023). Physiological assessment findings in this disorder include disinhibition, loss of executive functioning, memory loss in late-stage disease, and loss of fundamental emotions. Patients with this disorder may exhibit changes in behavior related to social life, spiritual beliefs, and political status (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). Psychiatric findings include impaired comprehension, incoherent speech, and compulsive behaviors (Antonioni et al., 2023). Poor perceptions and subsequent stigma are a cultural consideration for the disorder. Prayer and meditation are likely spiritual considerations for the disorders, as patients tend to find hope from spirituality during the later stages of the disease. Family is a biopsychosocial consideration for frontotemporal dementia, as the family is a source of psychosocial support for patients diagnosed with the disorder. The disorder is progressive with a fair to poor prognosis. The average life expectancy is 6-11 years after symptoms are noted and usually 3-4 years after the official diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2022).

Anticipated Prognosis of AD

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. The disease has a fair to poor prognosis as it has no cure. Individuals aged 65 and above diagnosed with the disease may have a life expectancy of up to eight years. However, the prognosis is fair, with a life expectancy of up to 20 years, if the disease is detected early and the affected individuals are started on medications.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Comprehensive management of Alzheimer’s Disease integrates non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Non-pharmacological interventions target the presenting manifestations of the disease and aim to improve the quality of life of patients with the disease. Several non-pharmacological treatment approaches that can be used to treat the behavioral, emotional, psychological, and environmental components of AD exists. These include but are not limited to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral management therapy (BMT), memory training, psychotherapy, and alternative therapies.

Cognitive behavioral therapy(CBT) remains effective in improving wellness and controlling some of the neuropsychiatric manifestations of Alzheimer’s. It may be used in the early stages of the disease to help individuals adjust to AD diagnosis, as well as plan for therapy. CBT also addresses neuropsychiatric symptoms apparent in AD, such as depression and anxiety. According to Li et al. (2022), CBT is effective in treating depression and can be used to manage depressive episodes in AD. It can thus be used to address the loss of interest reported in the patient case presented.

Behavioral management therapy (BMT) can also help address behavioral challenges that is sometimes seen in patients with AD. BMT targets behaviors, such as wandering, repetitive questioning, and agitation, that is sometimes apparent in patients with a diagnosis of AD. Commonly used BMT techniques are personalized activities, such as exercise and socialization and music and art therapies. BMT techniques alleviate disruptive behavior. They can be tailored to address the identified challenging behavioral pattern, thereby improving the wellness and quality of life of patients with dementia (Li et al., 2022). BMT techniques can be used to address wandering reported in Mr. John’s case.

Memory training may also be applied in patients with dementia. Memory training maximizes the cognitive functioning of patients with AD and other forms of dementia. It is effective in the early stages of AD but has little or no impact on cognitive functionalities in the later stages of the disease (Li et al., 2022). Memory training can improve daily functioning and tasks management in AD patients. Memory training can be used in Mr. John’s case to promote his independence in performing activities of daily living.

Psychotherapy and psycho-educational measures are other modalities used in patients with dementia. Psychotherapy finds use in patients with AD and their immediate caregivers. To the patients, psychotherapeutic interventions, such as talk therapy, may give the patients a chance to speak their minds freely, thereby promoting their emotional wellness. This will further help them adjust to their diagnosis and subsequently take proactive measures towards care. To the family members and caregivers, psychotherapy and psycho-educational measures may assist them in coping with caring for patients with AD. Psycho-educational interventions promote self-care by equipping the patient and family with the self-care skills necessary for AD (Li et al., 2022). In the case presented, psychotherapy and psycho-educational measures will allow the patient to adjust to the diagnosis, have the prerequisite self-care skills necessary for health and wellness maintenance, and expand the carer’s ability to cope with caring for the patient.

Alternative therapies also find use in AD. Alternative therapeutic modalities such as light massage and aromatherapy can help address insomnia apparent in AD. Diet is another alternative therapy that has some modulating effects on AD. Diet, especially Mediterranean diets, improves memory and cognitive functionalities in people with dementia (Li et al., 2022). Likewise, diets such as fish, poultry, and whole grain products have been thought to improve mental performance and can thus be used to improve cognitive and memory functionalities in persons with AD.

Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacotherapy in AD focuses on symptomatic treatment and delaying disease progression. Several pharmacotherapeutic interventions are available for use in AD. These medications can be stratified into cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, and partial N-Methyl-D Aspratate (NMDA) antagonists, such as memantine. Disease-modifying agents are other therapeutic agents that reverse the underlying pathophysiological processes resulting in AD.

Cholinesterase inhibitors increase the level of acetylcholine in the brain. Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, are approved by the FDA for treating AD and other forms of dementia. These medications can improve the cognitive, memory, and learning functionalities in Alzheimer’s (Conti Filho et al., 2023). Donepezil is the preferred medication in patients with AD but can also be used in other forms of dementia. It is administered in once-daily dosing and is thus best suited for the patient in the case presented. Rivastigmine and galantamine are other cholinesterase inhibitors that can be used in AD. They are preferred when the response to donepezil is suboptimal or when patients are unable to take donepezil (Conti Filho et al., 2023).

Memantine is an NMDA antagonist. It can be used to retard neurotoxicity associated with neurodegenerative disorders such as AD. Memantine can be used in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil. It has been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe AD (Conti Filho et al., 2023).

Disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease medications reverse the pathophysiological processes resulting in AD. They slow the progress of AD. They, however, have not been shown to produce a cure for AD. Lecanemab and Aducanemab are some of the available FDA-approved medications for use in AD. These medications are monoclonal antibodies that act by removing amyloid plaques in the brain, lowering the beta-amyloid burden (Conti Filho et al., 2023).

Comparison

Comprehensive management of Lewis Body Dementia (LBD) integrates pharmacotherapeutic and non-pharmacotherapeutic modalities. Galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil are the mainstay pharmacotherapy in LBD. These medications improve the quality of life in patients with LBD by helping in symptomatic control. This highlights their use in the LBD. Carbidopa-levodopa can also be used to treat motor symptoms of the LBD. Other drugs that can be used in symptomatic control of LBD include clonazepam for sleep disruptions, SSRIs for depressive episodes, and atypical antipsychotics for hallucinations (Tahami Monfared et al., 2019). Non-pharmacological interventions can be used together with pharmacotherapy for optimal symptom control in LBD. Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, exercise, and diet, such as Mediterranean diets, poultry, fish, and whole grains, can also help improve wellness in LBD (Tahami Monfared et al., 2019).

A combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions can also be used in the comprehensive management of Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and NMDA antagonists have a limited role in FTD. This is because they only improve some symptoms of the disease but not cognition. Antipsychotic medications also have a limited role in the disease and can only be used in the presence of hallucinations. Non-pharmacological measures, such as physiotherapy, are the mainstay therapeutic modalities in FTD. These interventions help in improving mobility and promoting relaxation in patients with dementia. They also improve behavioral symptoms of FTD (Magrath Guimet et al., 2022).

Special Considerations

Special considerations are given when prescribing anti-AD medications among older adults. Older adults with dementia are often started on low doses of donepezil to minimize side effects. Regular monitoring is warranted, and medication should only be started when monitoring is assured (Conti Filho et al., 2023). Donepezil can be administered in patients with renal impairment as the clearance of the drug is not affected in renal disease. Caution should be taken when starting older patients on galantamine, as it cannot be used in persons with end-stage renal disease and hepatic dysfunction. Lastly, as suggested by Conti Filho et al. ( 2023), low doses of rivastigmine, preferably 3-6 mg, are recommended when starting older adults with dementia.

References

Abubakar, M. B., Sanusi, K. O., Ugusman, A., Mohamed, W., Kamal, H., Ibrahim, N. H., Khoo, C. S., & Kumar, J. (2022). Alzheimer’s disease: An update and insights into pathophysiology. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.742408

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing

Antonioni, A., Raho, E. M., Lopriore, P., Pace, A. P., Latino, R. R., Assogna, M., Mancuso, M., Gragnaniello, D., Granieri, E., Pugliatti, M., Di Lorenzo, F., & Koch, G. (2023). Frontotemporal dementia, where do we stand? A narrative review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(14), 11732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411732

Boland, R., Verduin, M. L., & Ruiz, P. (2022). Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry. Wolters Kluwer.

Breijyeh, Z., & Karaman, R. (2020). A comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: Causes and treatment. Molecules, 25(24), 5789. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25245789

Conti Filho, C. E., Loss, L. B., Marcolongo-Pereira, C., Rossoni Junior, J. V., Barcelos, R. M., Chiarelli-Neto, O., Silva, B. S., Passamani Ambrosio, R., Castro, F. C., Teixeira, S. F., & Mezzomo, N. J. (2023). Advances in alzheimer’s disease’s pharmacological treatment. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1101452

Haider A, Spurling BC, Sánchez-Manso JC. Lewy Body Dementia. [Updated 2023 Feb 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482441/

Li, X., Ji, M., Zhang, H., Liu, Z., Chai, Y., Cheng, Q., Yang, Y., Cordato, D., & Gao, J. (2022). Non-drug therapies for alzheimer’s disease: A Review. Neurology and Therapy, 12(1), 39–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00416-x

Li, Y.-Q., Yin, Z.-H., Zhang, X.-Y., Chen, Z.-H., Xia, M.-Z., Ji, L.-X., & Liang, F.-R. (2022). Non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis protocol. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1039752

Magrath Guimet, N., Zapata-Restrepo, L. M., & Miller, B. L. (2022). Advances in treatment of frontotemporal dementia. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 34(4), 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.21060166

Menšíková, K., Matěj, R., Colosimo, C., Rosales, R., Tučková, L., Ehrmann, J., Hraboš, D., Kolaříková, K., Vodička, R., Vrtěl, R., Procházka, M., Nevrlý, M., Kaiserová, M., Kurčová, S., Otruba, P., & Kaňovský, P. (2022). Lewy body disease or diseases with Lewy bodies? Npj Parkinson’s Disease, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-021-002739

Prasad, S., Katta, M. R., Abhishek, S., Sridhar, R., Valisekka, S. S., Hameed, M., Kaur, J., & Walia, N. (2023). Recent advances in Lewy body dementia: A comprehensive review. Disease-a-month: DM, 69(5), 101441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.disamonth.2022.101441

Rosselli, M., Uribe, I. V., Ahne, E., & Shihadeh, L. (2022). Culture, ethnicity, and level of education in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics, 19(1), 26–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-022-01193-z

Tahami Monfared, A. A., Meier, G., Perry, R., & Joe, D. (2019). Burden of disease and current management of dementia with Lewy bodies: A literature review. Neurology and Therapy, 8(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00154-7

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

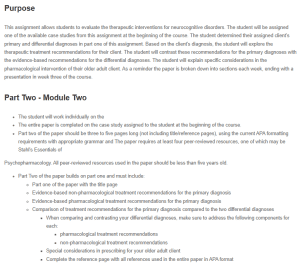

Purpose

This assignment allows students to evaluate the therapeutic interventions for neurocognitive disorders. The student will be assigned one of the available case studies from this assignment at the beginning of the course. The student determined their assigned client’s primary and differential diagnoses in part one of this assignment. Based on the client’s diagnosis, the student will explore the therapeutic treatment recommendations for their client. The student will contrast these recommendations for the primary diagnoses with the evidence-based recommendations for the differential diagnoses. The student will explain specific considerations in the pharmacological intervention of their older adult client. As a reminder the paper is broken down into sections each week, ending with a presentation in week three of the course.

Neurocognitive Case Study – Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

Part Two – Module Two

- The student will work individually on the

- The entire paper is completed on the case study assigned to the student at the beginning of the course.

- Part two of the paper should be three to five pages long (not including title/reference pages), using the current APA formatting requirements with appropriate grammar and The paper requires at least four peer-reviewed resources, one of which may be Stahl’s Essentials of

Psychopharmacology. All peer-reviewed resources used in the paper should be less than five years old.

- Part Two of the paper builds on part one and must include:

- Part one of the paper with the title page

- Evidence-based non-pharmacological treatment recommendations for the primary diagnosis

- Evidence-based pharmacological treatment recommendations for the primary diagnosis

- Comparison of treatment recommendations for the primary diagnosis compared to the two differential diagnoses

- When comparing and contrasting your differential diagnoses, make sure to address the following components for each:

- pharmacological treatment recommendations

- non-pharmacological treatment recommendations

- Special considerations in prescribing for your older adult client

- Complete the reference page with all references used in the entire paper in APA format

- When comparing and contrasting your differential diagnoses, make sure to address the following components for each: