Discussion – Doula Reimbursement

Abstract

Doulas provide supportive care during pregnancy, labor, and, to some extent, after childbirth. Doula services support maternal health service delivery and outcomes. However, reimbursement for doula services has not been widely incorporated into coverage services, including Medicaid services across all states. Only 12 states currently provide Medicaid coverage for doula care. Thus, the purpose of this review paper is to consolidate research on the impact of doula reimbursement and related policies. It aims to distill key achievements in maternal care with reimbursement of doulas and develop key policy recommendations for future research and for policymakers and advocates to guide a nationwide inclusion of doula care as a Medicaid-covered benefit. A database search was done in PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles published between July 1, 2018, and July 10, 2024, guided by the research question, “Do doula reimbursement policies improve doula services access and maternal health outcomes?” and a systematic review conducted utilizing PRISMA guidelines. Eleven articles met the inclusion criteria. Three themes were identified from the review: a) doula reimbursement reduces maternal and childbirth health inequities, b) doulas improve the cost-effectiveness of maternal care, and c) doula reimbursement policies improve health equity in maternal and birth outcomes. This review concludes that doulas provide important support services among birthing people and recommends the formulation or modification of and the implementation of policies that support doula care services as Medicaid-covered benefits across all States.

Keywords: doulas, doula reimbursement, maternal and childbirth outcomes

Doula Reimbursement

Background

The United States’ healthcare system still struggles with poor maternal health outcomes during and post-pregnancy. Despite the multisectoral efforts that have seen some improvements in the overall well-being of women, especially pregnant mothers and infants, data shows that the US, compared to other OECD countries, has the highest maternal mortality rates (Belluz 2020). The US experiences the most social disparities in access to maternal health services and inequalities in maternal mortality rates among the OECD countries (Singh, 2021). The causal factors to poor maternal and childbirth outcomes in the US are multifactorial. For example, most disparities are attributed to gendered racism, with women of color having the worst outcomes as compared to their white counterparts during pregnancy and childbirth. Black people, compared to other racial groups, especially Whites, tend to have more negative health outcomes during and after pregnancy, including preterm labor, excess bleeding, and gestational diabetes (Bornstein et al., 2020). Notably, racial minorities, including Blacks and ethnic indigenous groups, are twice as likely to die as a result of pregnancy-related complications or childbirth as compared to Whites (Petersen et al., 2019). Preterm births are also an issue of concern in maternal health, with significantly notable racial disparities. This is despite the United States the highest expenditure on healthcare (Karaman et al., 2020).

Besides gendered racism and other systemic barriers that have caused challenges for various groups regarding accessing the best quality maternal and childbirth care in an equitable manner, there has been the current workforce shortage. The United States is facing a healthcare workforce crisis with a major shortage of nurses and specialists. Among this workforce shortage is the shortage of qualified midwives. It is estimated that the world is currently experiencing a shortage of midwives by 900,000, which is projected to drop to 750,000 by 2030 (Nove et al., 2021). As compared to other developed and high-income countries, women, regardless of race, are less likely to receive midwifery services during and after birth. The US currently has four midwives for every 1,000 live births, while other high-income countries provide from 40 to 70 for every 1,000 live births (Combellick et al., 2023). This shortage means that a majority of women fail to access the needed emotional, mental, and physical assistance and care during pregnancy and after childbirth.

Arguably, the period throughout pregnancy is a time for physical and emotional change, including significant experience of increased risk of mental illness (Bedaso et al., 2021). Mental and emotional support and well-being are essential to a successful pregnancy, as well as maternal and child outcomes. Generally, it is estimated that over 700 Americans die due to pregnancy-related complications. Out of these maternal deaths, 11 percent were directly related to underlying mental health issues (Trost et al., 2021). Additionally, 63 percent of these are related to suicide (Trost et al., 2021). Depression and anxiety have been identified as the most common mental health conditions affecting a majority of pregnant women in the United States, which has contributed to a majority of suicide and self-harm behaviors, leading to high maternal deaths. A recent umbrella review focused on examining the global and regional burden of antenatal depression and reported an estimated 17% prevalence in high-income countries (Dadi et al., 2020). On the other hand, a systematic review by Bedaso et al. (2021) links access to social and mental health support to reduced complications during pregnancy, including prevention of depression and related instances of suicide and self-harm. Such support, if extended to post-pregnancy periods, has been associated with reduced instances of complications and depression.

Secondly, the childbirth process, from caring for the pregnancy to delivery and the post-partum period, is among the major contributors to health costs. For instance, childbirth is a major reason for hospitalization in the US, with maternity care contributing to the excess of hospital expenses. The expenses tend to be based on the mode of delivery. Cesarean delivery costs more and has a higher risk profile. Noting that pregnancy causes significant physical and emotional change and the development of mental illness (Bedaso et al., 2021), the risks and costs go higher, especially for individuals with limited access to professional services. The financial risk of childbirth care has pushed for the consideration and adoption of various policy initiatives in the US to ensure sufficient access to pregnancy and childbirth care. One initiative has been investing in the training of nurses with midwifery competencies. Other policies include the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which supports access to midwifery services via Medicaid coverage. However, with an estimated 3.6 million women giving birth in the US annually (Knocke et al., 2022), the available number of midwives currently in services within the US health systems do not meet the current demand, and the higher costs of utilizing midwifery services during pregnancy reduce the rates of utilization of such professional care services. This has further pushed for the development and adoption of low-cost interventions to provide support for pregnancy and post-birth care. This has led to the growth of the birth doula as a low-cost intervention.

Doulas are maternal care providers with varying degrees of training and are professionals. They provide various support care services to mothers prior to, during, and after childbirth, such as emotional, physical, and mental support (Knocke et al., 2022). These services are also integrated with pregnancy education to mothers during pregnancy on self-care and supporting necessary exercises. Available literature links doula services to improved pregnancy, birth, and post-partum outcomes. For instance, a study conducted within a female prison setting involving incarcerated pregnant women and the provision of doula support reported that despite a majority of the women having limited educational attainment and with higher rates of exposure to physical and mental health issues, the mothers gave birth to healthy newborns in full-term gestation, right birth weight, and without the need to a C-section (Shlafer et al., 2021). More evidence from England with the use of doulas shows that, although under voluntary terms, doulas provided enough support to pregnant mothers, helping them overcome mental issues such as stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, as well as providing them with informational resources to help them improve on their self-efficacy and utilize services effectively (McLeish & Redshaw, 2019). Additionally, the utilization of doula services throughout the continuum of maternity care leads to better overall maternal and childbirth outcomes. For example, a three-state study by Falconi et al. (2022) reports that the use of doula services during the pregnancy period at any trimester reduces cesarean delivery by over 52.9% and post-partum depression and anxiety by an estimated 58%. It also reports that the use of doula services during labor and childbirth periods reduces the risk of post-partum depression and anxiety and the risk of other mental issues by 65%.

However, despite the proven potential of doulas to improve maternal and childbirth outcomes, the integration of doula services into the healthcare system through Medicaid reimbursement is yet to be realized in the US. So far, only 17 States have made varying efforts to fully implement the Medicaid doula reimbursement program. Out of these, only six, including Oregon, Minnesota, New Jersey, Florida, Maryland, and Virginia, had fully integrated the reimbursement for doula services into Medicaid by 2022, while states like California, Washington DC, Illinois, Indiana, Nevada, and Rhode Island have achieved some progress in approving doula coverage under Medicaid as of 2023 (Knocke et al., 2022). Others, such as Arizona, Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, and Washington, are actively considering the implementation of the doula program in Medicaid. This means a majority of the states do not provide coverage for such serving. With the fact that doula service can cost up to $1,500 per pregnancy (Knocke et al., 2022), a majority of populations, especially those from low-income households—with racial and ethnic minorities forming a large part of this social groups—may miss out on the access to such important doula services.

The doula reimbursement programs have the potential to not only improve maternal and childbirth outcomes but also address the disparities existing in maternal healthcare in the US. This systematic review aims to review the current literature on the impact of doula reimbursement efforts to develop evidence to inform doula reimbursement policy recommendations for wider adoption across all states and further improve maternal healthcare. Guided by the research question, “Do doula reimbursement policies improve doula services access and maternal health outcomes?” the review searches for and analyzes research articles specifically in the US focused on doula reimbursement and effects on cost-effectiveness in equity, access, and childbirth and maternal outcomes.

Data and Method

Design

A systematic literature review was conducted to explore current evidence on doula reimbursement policies guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Pati & Lorusso, 2018). The systematic review followed the 7-step approach for SRs: a) research question formulation, b) definition of search protocol, c) definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria, d) screening studies for eligibility, e) assessing quality, e) synthesis and data analysis, and f) interpretation and discussion of results.

Search Methods

The search was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles published between July 1, 2018, and July 10, 2024. Key terms using MeSH terms for the search included “doula,” “doula reimbursement,” “doula policies,” “birth support,” and “doula care policies.” Boolean operations were also used to expand the search results.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the review based on various categories: a) results were relevant to doula-related policies, b) results were relevant to doula-related reimbursement, c) studies specifically done in the United States. Studies were excluded based on: a) not peer-reviewed, b) not published within the last five years, c) not a full-text article, and d) not focused on doula services in the US.

Screening for Eligibility

All studies were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The screening was first based on the study’s title and abstract. Due to the limited number of available studies, the screening for the selected studies included a full review of the entire text.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the studies was appraised based on the relevance of the study to the topic and the research question, the author’s credibility, methodological validity and reliability, clarity of findings, and the comprehensiveness of each study’s references list.

Data Extraction, Synthesis, and Analysis

The metadata of all included articles was extracted manually. Synthesis also included a review of methods and design, participants, and setting. Themes and trends on doula policies were identified based on thematic analysis utilizing an inductive and deductive approach.

Findings/Discussion

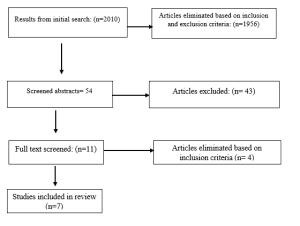

The search based on the defined protocol returned a total of 2010 articles. Notably, 1956 articles were removed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, thus remaining with 54 articles. Further, reports and other articles considered not directly related to doula reimbursement were eliminated, thus leaving 12 articles. Out of these, only ten were included in the final review.

Of the seven articles, a majority were qualitative studies (n=4), quantitative (n=2), and mixed methods (n=1). The consideration of the demographics of the sample population was not done. The analysis focused on the identifiable themes in each article. The articles were then grouped into two categories based on the identified theme: a) doula reimbursement policies reduce maternal and childbirth health inequities (n=5), and b) doulas improve the cost-effectiveness of maternal care (n=2).

The articles focused on doula reimbursement policies in the reduction of maternal and childbirth health inequities and explored ways in which policy and funding programs such as doula Medicaid reimbursement addressed the issues of health inequities and access to maternal care. Articles focused on how doulas improve the cost-effectiveness of maternal care and explored how such policies impact the cost of care during pregnancy and childbirth.

Doula Reimbursement Policies in Reducing Maternal and Childbirth Health Inequities

Four articles focused on how doula reimbursement policies address racial and other social inequalities in access to maternal care and birth outcomes in the United States (Knight & Rich, 2024; Ogunwole et al., 2022; Safon et al., 2024; Van Eijk et al., 2022). One study directly focused on the analysis of doula-related bills and their focus on addressing health equity in the US. (Ogunwole et al., 2022). The article reports that there has been a three-fold increase in the introduction of doula-related state legislation, with 53.4% of such legislation focused on introducing measures for the reimbursement of doula services as a Medicaid coverage benefit. However, out of the 58 introduced bills for Medicaid reimbursement for doulas as of 2020, only two states, Virginia and Oregon, included clauses addressing existing racial inequities in maternal and childbirth outcomes.

One article focused on approaches to address the systemic racism that affects doula services and fuels health inequities in the US (Van Eijk et al., 2022). The article proposes systems-level changes to support equitable growth of doula services. The authors propose a state-level legislative action as a solution to address structural racism and support a cautious approach to decision-making and policymaking with regard to Medicaid reimbursement (Van Eijk et al., 2022).

One article compared doula-related policies from two states, Oregon, which has doula services reimbursed, and Massachusetts, with pending implementation of doula Medicaid reimbursement, to determine how such policies contributed to the accessibility of perinatal doula services (Safon et al., 2024). The article also identified the various barriers and facilitators to Medicaid reimbursement based on how doula-related policies were perceived. The article reports that stakeholders understand the need and benefits of expanding access to doula services. However, there are multiple challenges to achieving the expansion of doula services, including a lack of recognition and value for doula services within the health care system, a complex billing process, the lack of clear doula services structure complicating policymaking, and structural fragmentation between the state government and doula communities further complicating policymaking (Safon et al., 2024).

The other article discusses the themes policymakers need to consider in the expansion of doula services and addressing inequalities in maternal and infant health (Knight & Rich, 2024). The authors suggest further training of doulas with a focus on cultural competence and collaborative practice; they also suggest doula reimbursement policies to include logistical, administrative, and financial considerations for policy and practice change (Knight & Rich, 2024).

Doulas Improve the Cost-Effectiveness of Maternal Care

Two articles focused on the cost-effectiveness of maternal care due to the use of accessible doula services (Gebel et al., 2024; Mosley et al., 2023). Both articles link doula services to improved maternal and childbirth outcomes. They also identify reimbursement for the provided doula services as a major challenge to the accessibility and utilization of such services. For example, Mosley et al.’s (2023) article notes that doulas are willing to serve racial, ethnic, and other social minority groups; however, they feel that despite serving a number of clients, they are underpaid for their services. Based on the results of their study, the authors suggest the adoption and integration of Medicaid reimbursement and community health worker models within local healthcare systems to improve the equitability of access to doula care (Mosley et al., 2023). Expanding doula care will require the use of empirical and anecdotal evidence, the recognition of the resource-intensiveness of doula care implementation, and a whole-systems approach involving support from midwives and other professionals (Gebel et al., 2024).

Conclusions/Policy Implications

This review aimed to review and present evidence on the impact of doula reimbursement efforts, including the impact of doula reimbursement policies on improving doula services and maternal health and childbirth outcomes. The findings suggest that doula-related reimbursement policies can promote wider access and utilization of doula services by addressing existing racial and socioeconomic inequalities in maternal and childbirth outcomes. However, research in doula-related reimbursement in the US is still underdeveloped. There is a need to conduct a comparative analysis of current doula reimbursement programs against states without such policies. Policymakers will also need to work collaboratively with stakeholders to identify and address the various challenges and opportunities to establish equitable and robust doula care policies. Noting that a significant amount of evidence points out that doula care can improve maternal health and childbirth outcomes and reduce racial inequities among racial minorities and low-income women, there is a need for advocacy across all states to implement Medicaid reimbursement for doula services.

References

Bedaso, A., Adams, J., Peng, W., & Sibbritt, D. (2021). The relationship between social support and mental health problems during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Health, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01209-5

Bornstein, E., Eliner, Y., Chervenak, F. A., & Grünebaum, A. (2020). Racial disparity in pregnancy risks and complications in the US: Temporal changes during 2007–2018. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM9051414

Combellick, J. L., Telfer, M. L., Ibrahim, B. B., Novick, G., Morelli, E. M., James-Conterelli, S., & Kennedy, H. P. (2023). Midwifery care during labor and birth in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S983–S993. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2022.09.044

Dadi, A. F., Miller, E. R., Bisetegn, T. A., & Mwanri, L. (2020). Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-020-8293-9

Falconi, A. M., Bromfield, S. G., Tang, T., Malloy, D., Blanco, D., Disciglio, R. S., & Chi, R. W. (2022). Doula care across the maternity care continuum and impact on maternal health: Evaluation of doula programs across three states using propensity score matching. EClinicalMedicine, 50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101531

Gebel, C., Larson, E., Olden, H. A., Safon, C. B., Rhone, T. J., & Amutah-Onukagha, N. N. (2024). A qualitative study of hospitals and payers implementing community doula support. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/JMWH.13596

Karaman, S., Ürek, D., Bilgin Demir, İ., Uğurluoğlu, Ö., & Işık, O. (2020). The impact of healthcare spending on health outcomes: New evidence from OECD countries. Journal of Clinical Practice and Research, 42(2), 218-. https://doi.org/10.14744/ETD.2020.80393

Knight, E. K., & Rich, R. (2024). “We are all there to make sure the baby comes out healthy”: A qualitative study of doulas’ and licensed providers’ views on doula care. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 10(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.32481/DJPH.2024.03.08

Knocke, K., Chappel, A., Sugar, S., De Lew, N., & Sommers, B. D. (2022). Doula care and maternal health: An evidence review. In ISSUE BRIEF. https://www.marchofdimes.org/research/maternity-care-deserts-report.aspx.

McLeish, J., & Redshaw, M. (2019). “Being the best person that they can be and the best mum”: A qualitative study of community volunteer doula support for disadvantaged mothers before and after birth in England. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12884-018-2170-X/TABLES/1

Mosley, E. A., Lindsey, A., Turner, D., Shah, P., Sayyad, A., Mack, A., & Lindberg, K. (2023). “I want…to serve those communities…[but] my price tag is…not what they can afford”: The community-engaged Georgia doula study. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 55(3), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1363/PSRH.12241

Nove, A., ten Hoope-Bender, P., Boyce, M., Bar-Zeev, S., de Bernis, L., Lal, G., Matthews, Z., Mekuria, M., & Homer, C. S. E. (2021). The state of the world’s midwifery 2021 report: Findings to drive global policy and practice. Human Resources for Health, 19(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12960-021-00694-W

Ogunwole, S. M., Karbeah, J. M., Bozzi, D. G., Bower, K. M., Cooper, L. A., Hardeman, R., & Kozhimannil, K. (2022). Health equity considerations in state bills related to doula care (2015–2020). Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 32(5), 440. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WHI.2022.04.004

Pati, D., & Lorusso, L. N. (2018). How to write a systematic review of the literature. Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 11(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586717747384/SUPPL_FILE/HOW_TO_WRITE_A_SYSTEMATIC_REVIEW_OF_THE_LITERATURE.PDF

Petersen, E. E., Davis, N. L., Goodman, D., Cox, S., Syverson, C., Seed, K., Shapiro-Mendoza, C., Callaghan, W. M., & Barfield, W. (2019). Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths — United States, 2007–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(35), 762–765. https://doi.org/10.15585/MMWR.MM6835A3

Safon, C. B., McCloskey, L., Estela, M. G., Gordon, S. H., Cole, M. B., & Clark, J. (2024). Access to perinatal doula services in Medicaid: A case analysis of 2 states. Health Affairs Scholar, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/HASCHL/QXAE023

Shlafer, R., Davis, L., Hindt, L., & Pendleton, V. (2021). The benefits of doula support for women who are pregnant in prison and their newborns. In Children with Incarcerated Mothers: Separation, Loss, and Reunification (pp. 33–48). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67599-8_3

Singh, G. K. (2021). Trends and social inequalities in maternal mortality in the United States, 1969-2018. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health and AIDS, 10(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.21106/IJMA.444

Trost, S. L., Beauregard, J. L., Smoots, A. N., Ko, J. Y., Haight, S. C., Simas, T. A. M., Byatt, N., Madni, S. A., & Goodman, D. (2021). Preventing pregnancy-related mental health deaths: Insights from 14 US maternal mortality review committees, 2008–17. Health Affairs, 40(10), 1551–1559. https://doi.org/10.1377/HLTHAFF.2021.00615

Van Eijk, M. S., Guenther, G. A., Kett, P. M., Jopson, A. D., Frogner, B. K., & Skillman, S. M. (2022). Addressing systemic racism in birth doula services to reduce health inequities in the United States. Health Equity, 6(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1089/HEQ.2021.0033

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

The length of the paper is about 10 pages in double space. Your paper is expected to include at least 10 scholarly sources and contain the following components or sections. You may choose to organize your paper using subheadings for the following:

Discussion – Doula Reimbursement

Abstract – one paragraph stating your research question, the type of information you examined, how you analyzed the data, and your findings.

Problem statement and research objective: Why is your topic important? The problem statement conveys a brief overview of the background/context of your research questions. The research objective should be specified. Your work will either provide an answer to explain the problems selected (to the why question) and/or provide policy implications.

Literature review: You are supposed to do a proper literature review on publications on your research question, analyzing research trends (e.g., hot issues, unsolved problems) as evidences for your sufficient understanding on your research topic.

Data and method: What type of data/information will you use and how will you use them to answer the research question? For example, will your analysis consist of a quantitative review of related research or other relevant information? Or will your analysis be more qualitative? (Empirical work is preferred).

Analysis: Do your own analysis using proper methods.

Findings/Discussion: What is the ‘answer’ to your research question? Try to elaborate a bit on the ‘whys’ relating to your findings. This is the section to speculate a bit based on your findings through your research.

Conclusions/Policy implications: Simply reiterate your findings and offer suggestions for future research or for better policy in your topic area.