Differentiation in a Classroom

Kids of the same age aren’t all alike when it comes to learning more than they are alike in size, hobbies, personality, or food preferences. Kids have many things in common because they are human beings and all young people, but they also have important differences. What we share makes us human, but how we differ makes us individuals. Only student similarities seem to take center stage in a classroom with little or no differentiated instruction. Commonalities are acknowledged and built upon in a differentiated classroom, and student differences are important in teaching and learning.

At its basic level, differentiating instruction means “shaking up” what goes on in the classroom so that students have multiple options for taking in information, making sense of ideas, and expressing what they learn. In other words, a differentiated classroom provides different avenues to acquiring content, processing or making sense of ideas, and developing products so that each student can learn effectively.

In many classrooms, the approach to teaching and learning is more unitary than differentiated. For example, 1st graders may listen to a story and then draw pictures of the story’s beginning, middle, and end. While they may choose to draw different aspects of the elements, they all experience the same content and engage in the same sense-making or processing activity. A kindergarten class may have four centers that all students visit to complete the same weekly activities. Fifth graders may listen to the same explanation about fractions and complete the same homework assignment. Middle or high school students may sit through a lecture and a video to help them understand a topic in science or history. They will all read the same chapter, complete the same lab or end-of-chapter questions, and take the same quiz—all on the same timetable. Such classrooms are familiar, typical, and largely undifferentiated.

Most teachers (students and parents) have clear mental images of such classrooms. After experiencing undifferentiated instruction over many years, it is often difficult to imagine what a differentiated classroom would look and feel like. How educators wonder, can we shift from “single-size instruction” to differentiated instruction to better meet our students’ diverse needs? To answer this question, we first need to clear away some misperceptions.

What Differentiated Instruction Is NOT

Differentiated instruction is NOT “individualized instruction.”

Decades ago, in an attempt to honor students’ learning differences, educators experimented with “individualized instruction.” The idea was to create a different, customized lesson each day for each of the 30-plus students in a single classroom. Given the expectation that each student needed a different reading assignment, for example, it didn’t take long for teachers to become exhausted. A second flaw in this approach was that to “match” each student’s precise entry level into the curriculum with each upcoming lesson, instruction needed to be segmented or reduced into skill fragments, thereby making learning largely devoid of meaning and essentially irrelevant to those who were asked to master the curriculum.

While it is true that differentiated instruction can offer multiple avenues to learning, and although it certainly advocates attending to students as individuals, it does not assume a separate assignment for each learner. It also focuses on meaningful learning—on ensuring all students engage with powerful ideas. Differentiation is more reminiscent of a one-room schoolhouse than of individualization. That model of instruction recognized that the teacher needed to work sometimes with the whole class, sometimes with small groups, and sometimes with individuals. These variations were important to move each student along in their particular understanding and skills and to build a sense of community in the group.

Differentiated instruction is NOT chaotic.

Most teachers remember the recurrent, nightmarish experience from their first year of teaching: losing control of student behavior. A benchmark of teacher development is the point at which the teacher becomes secure and comfortable with managing classroom routines. Fear of returning to uncertainty about “control of student behavior” is a major obstacle for many teachers in establishing a flexible classroom. Here’s a surprise, though: teachers who differentiate instruction quickly point out that, if anything, they now exert more leadership in their classrooms, not less. And student behavior is considerably more focused and productive.

Compared with teachers who offer a single approach to learning, teachers who differentiate instruction have to be more active leaders. Often they must help students understand how differentiation can support greater growth and success for everyone in the class and then help them develop ground rules for effective work in classroom routines—all while managing and monitoring the multiple activities that are going on.

Effectively differentiated classrooms include purposeful student movement and sometimes purposeful student talking, but they are not disorderly or undisciplined. On the contrary, “orderly flexibility” is a defining feature of differentiated classrooms and any classroom that prioritizes student thinking. Research shows that neither “disorderly” nor ” restrictive ” environments support meaningful learning.

(Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2007).

Differentiated instruction is NOT just another way to provide homogeneous grouping.

Our memories of undifferentiated classrooms probably include the bluebird, cardinal, and buzzard reading groups. Typically, a predator remained a predator, and a cardinal was forever a cardinal. Under this system, buzzards nearly always worked with buzzards on skills-focused tasks, while work done by cardinals was typically at “higher levels” of thought. In addition to being predictable, student assignment to groups was virtually always teacher-selected.

A hallmark of an effective differentiated classroom, by contrast, is the use of flexible grouping, which accommodates students who are strong in some areas and weaker in others. For example, a student may be great at interpreting literature but not so strong in spelling, or great with map skills and not as quick to grasp patterns in history, or quick with math word problems but careless with computation. Teachers who use flexible grouping also understand that some students may begin a new task slowly and then launch ahead at remarkable speed, while others will learn steadily but more slowly. They know that sometimes they need to assign students to groups so that assignments are tailored to student needs but that, in other instances, it makes more sense for students to form their working groups. Some students prefer or benefit from independent work, while others usually fare best in pairs or triads.

In a differentiated classroom, the goal is to have students work consistently with a wide variety of peers and with tasks thoughtfully designed to draw on the strengths of all group members and shore up those students’ areas of need. “Fluid” is a good word to describe the assignment of students to groups in such a heterogeneous classroom. See the Appendix for more information on flexible grouping.

Differentiated instruction is NOT just “tailoring the same suit of clothes.”

Many teachers think they differentiate instruction when they let students volunteer to answer questions, grade some students a little harder or easier on an assignment in response to the students’ perceived ability and effort, or let students read or do homework if they finish a class assignment early. Certainly, such modifications reflect a teacher’s awareness of differences in student needs; in that way, the modifications are a movement toward differentiation. While such approaches play a role in addressing learner variance, they are examples of “micro-differentiation” or “tailoring” and are often insufficient to address significant learning issues adequately.

If the basic assignment is far too easy for an advanced learner, having a chance to answer an additional complex question is not an adequate challenge. If information is essential for a struggling learner, allowing him to skip a test question because he never understood the information does nothing to address the student’s learning gap. If the information in the basic assignment is simply too complex for a learner until she has the chance to assimilate needed background information or language skills, being “easier on her” when grading her assignment circumvents her need for additional time and support to master foundational content. In sum, trying to stretch a garment far too small or attempting to tuck and gather a garment far too large is likely to be less effective than getting clothes that are the right fit. Said another way, small adjustments in a lesson may be all that’s needed to make the lesson “work” for a student in some instances, but in many others, the mismatch between learner and lesson is too great to be effectively addressed in any way other than re-crafting the lesson itself.

Differentiated instruction is NOT just for outliers.

Certainly, students who have identified learning challenges such as autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, intellectual disabilities, visual impairment, and so on are likely to need scaffolding on a fairly regular basis to grow academically as they should.

Likewise, students who learn rapidly, think deeply, and readily make meaningful connections within or across content areas will need advanced challenges regularly as they should. And students who are just learning the language spoken in the classroom will typically require support as they seek to master both content and the language in which it is communicated. But in virtually any class on any day, there are students “in the middle” who struggle moderately, or just a little, with varied aspects of what they are seeking to learn.

Some students know a bit about a portion of a lesson or unit but struggle with specific steps or content. Some students’ experiences outside the classroom weigh negatively on their ability to concentrate or complete work. Some students are just about to “take flight” with an idea that has been out of their reach and needs encouragement and a boost to ensure their launch is successful. Every student benefits from being on the teacher’s radar and seeing evidence that the teacher understands their development and plans with their success in mind.

What Differentiated Instruction IS

Differentiated instruction IS proactive.

In a differentiated classroom, the teacher assumes that different learners have different needs and proactively plans lessons that provide a variety of ways to “get at” and express learning. The teacher may still need to fine-tune instruction for some learners, but because the teacher knows the varied learner needs within the classroom and selects learning options accordingly, the chances are greater that these experiences will be an appropriate fit for most learners. Effective differentiation is typically designed to be robust enough to engage and challenge the full range of learners in the classroom.

In a one-size-fits-all approach, the teacher must make reactive adjustments whenever it becomes apparent that a lesson is not working for some of the learners for whom it was intended.

For example, many students at all grade levels struggle with reading. Those students need a curriculum with regular, built-in, structured, and supported opportunities to develop the skills of competent readers. While it may be thoughtful and helpful in the short term for a teacher to provide both oral and written directions for a task so that students can hear what they might not be able to read with confidence, their fundamental reading problems are unlikely to diminish unless the teacher makes proactive plans to help students acquire the specific reading skills necessary for success in that particular content area.

Differentiated instruction IS more qualitative than quantitative.

Many teachers incorrectly assume that differentiating instruction means giving some students more work to do and others less. For example, a teacher might assign two book reports to advanced readers and only one to struggling readers. Or a struggling math student might have to complete only computation problems while advanced math students complete the computation problems plus a few word problems.

Although such approaches to differentiation may seem reasonable, they are typically ineffective. One book report may be too demanding for a struggling learner without additional concurrent support in reading and interpreting the text. Or a student who is perfectly capable of acting out what happened in the book might be overwhelmed by writing a three-page report. If writing one book report is “too easy” for the advanced reader, doing “twice as much” of the same thing is unlikely to remedy that problem but could also seem like punishment. A student who has already demonstrated mastery of one math skill is ready to stop practicing that skill and needs to begin work with a subsequent skill. Simply adjusting the quantity of an assignment will generally be less effective than altering the nature of the assignment to match the actual student’s needs.

Differentiated instruction IS rooted in assessment.

Teachers who understand that teaching and learning approaches must be a good match for students look for every opportunity to know their students better. They see conversations with individuals, classroom discussions, student work, observation, and formal assessment as ways to gain insight into what works for each learner. What they learn becomes a catalyst for crafting instruction to help students maximize their potential and talents.

In a differentiated classroom, assessment is no longer predominantly something that happens at the end of a unit to determine “who got it.” Diagnostic pre-assessment routinely occurs as a unit begins to shed light on individuals’ particular needs and interests concerning the unit’s goals. Throughout the unit, systematically and in various ways, the teacher assesses students’ developing readiness levels, interests, and approaches to learning and then designs learning experiences based on the latest, best understanding of students’ needs. Culminating products, or other means of “final” or summative assessment, take many forms to find a way for each student to most successfully share what they have learned throughout the unit.

Differentiated instruction IS taking multiple approaches to content, process, and product.

In all classrooms, teachers deal with at least three curricular elements: (1) content—input, what students learn; (2) process—how students go about making sense of ideas and information; and (3) product—output, or how students demonstrate what they have learned. These elements are dealt with in depth in Chapters 12, 13, and 14.

By differentiating these three elements, teachers offer different approaches to what students learn, how they learn, and how they demonstrate what they’ve learned. The different approaches have in common that they are crafted to encourage all students’ growth with established learning goals and to attend to pacing and other supports necessary to advance the learning of the class as a whole and individual learner.

Differentiated instruction IS student-centered.

Differentiated classrooms operate on the premise that learning experiences are most effective when engaging, relevant, and interesting to students. A corollary to that premise is that all students will not always find the same avenues to learning equally engaging, relevant, and interesting. Further, differentiated instruction acknowledges that later knowledge, skill, and understandings must be built on previous knowledge, skill, and understandings—and that not all students possess the same learning foundations at the outset of a given investigation. Teachers who differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms seek to provide appropriately challenging learning experiences for all students. These teachers realize that sometimes a task that lacks challenge for some learners is frustratingly complex to others.

In addition, teachers who differentiate understand the need to help students develop agency as learners. It’s easier sometimes, especially in large classrooms, for a teacher to tell students everything rather than guide them to think independently, accept significant responsibility for learning, and build a sense of pride in what they do. In a differentiated classroom, learners must actively make and evaluate decisions that benefit their growth. Teaching students to work wisely and share responsibility for classroom success enables a teacher to work with varied groups or individuals for portions of the day because students are self-directing. It also prepares students far better for life now and in the future.

Differentiated instruction IS a blend of whole-class, group, and individual instruction.

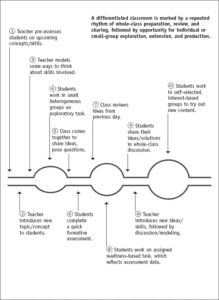

There are times in all classrooms when whole-class instruction is an effective and efficient choice. It’s useful for establishing common understandings, for example, and provides the opportunity for shared discussion and review that can build a sense of community. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the pattern of instruction in a differentiated classroom could be represented by mirror images of a wavy line, with students coming together as a whole group to begin a study, moving out to pursue learning in small groups or individually, coming back together to share and make plans for additional investigation, moving out again for more work, coming together again to share or review, and so on.

Figure 1.1. The Flow of Instruction in a Differentiated Classroom

Differentiated instruction IS “organic” and dynamic.

In a differentiated classroom, teaching is evolutionary. Students and teachers are learners together. While teachers may know more about the subject, they are continuously learning about how their students learn. Ongoing collaboration with students is necessary to refine learning opportunities to be effective for each student. Teachers monitor the match between learner and learning and make adjustments as warranted. And while teachers know that sometimes the learner/learning match is less than ideal, they also understand that they can continually make adjustments. This is an important reason why differentiated instruction often leads to more effective learner/learning matches than the mode of teaching that insists that one assignment serves all learners well.

Further, teachers in a differentiated classroom do not see themselves as someone who “already differentiates instruction.” Rather, they are fully aware that every hour of teaching and every day in the classroom can reveal one more way to make the classroom a better environment for its learners. Nor do such teachers see differentiation as “a strategy” or something to do once in a while or when there’s extra time. Rather, it is a way of life in the classroom. They do not seek or follow a recipe for differentiation; instead, they combine what they can learn about differentiation from a range of sources with their professional instincts and knowledge base to do whatever it takes to reach each learner.

A Framework to Keep in Mind

As you continue reading about how to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms, keep this framework in mind:

In a differentiated classroom, the teacher proactively plans and carries out varied approaches to content, process, and product in anticipation of and response to student differences in readiness, interest, and learning needs.

The explanations and examples in this book are presented to help populate this new framework for you as you work to differentiate instruction in your academically diverse classroom. Let’s get started with a closer look at the rationale for differentiation.

References

Carol Ann Tomlinson.; How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms Account: ns017578.main.eds

Tomlinson, C. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed ability classrooms. (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Respond to the following discussion item in 75-100 words.

Comment upon how this statement from pp. 5 –6 of the Tomlinson text featured this week relates to what should occur in your classroom and your school.

Differentiation in a Classroom

Please Respond…

“Differentiated instruction is dynamic: Teachers monitor the match between learner and learning and make adjustments as warranted. And while teachers know that sometimes the learner/learning match is less than ideal, they also understand that they can continually make adjustments. …. Differentiation …is a way of life in the classroom.

[The teacher] does not seek or follow a recipe… but combines what she can learn about differentiation from a range of sources to her professional instincts and knowledge base to do whatever it takes to reach out to each learner.”

Tomlinson, C. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed ability classrooms. (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.