Bullying of LGBTQIA Youths vs Heterosexual Youths

There has been evidence that LGBTQIA youths experience more bullying and are more vulnerable to suicide risk than their heterosexual counterparts. However, fewer research studies have analyzed whether the size of the LGBTQIA community affected by these outcomes has differed with time. This paper will examine the national trends in bullying as well as suicide attempts among school-age adolescents through self-reported sexual identity (heterosexual or LGBT) and compare the differences in these trends between male and female LGBT students. It will also compare these differences based on ethnicity or race, students who identify as a minority or not. This analysis will base its data on secondary sources, specifically from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) cycles from 2015, 2017, and 2019. This tool is a school-based cross-sectional survey carried out biennially since 1991. The CDC assessed trends in bullying and suicide risk rates among the LGBTQIA community and heterosexual students between 2015 and 2019. The results of this survey indicated that LGBTQIA students experienced more bullying electronically and physically and expressed more suicide rate behaviors than their heterosexual counterparts. Therefore, these results show that communities and schools need strategic interventions to minimize bullying and address suicide attempts and ideation among vulnerable LGBTQIA youths.

Introduction

LGBTQIA youth have shown higher rates of mental health issues and are more likely to engage in risky behaviors than heterosexual youth (Russell & Osher, 2001). Shield et al. (2012) find that these behaviors are linked with higher suicide attempts and ideation rates in youth. Moreover, school-aged youths who self-identify as LGBTQIA are three or two times more likely to self-report suicide attempts and ideation than heterosexual youth (Shields et al., 2012).

Research studies also show that exposure to violence and harassment may be additional risk factors that cause an increased suicide risk among LGBTQIA youths (Shields et al., 2012). This information shows more concern for the vulnerable community since LGBTQIA youths have reported forms of victimization like bullying and harassment at a higher rate than heterosexual youths. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) findings of 2017 showed that LGB adolescents in high school faced more bullying within the school compound. Thirty-three percent of LGB adolescent students reported having experienced bullying, whereas 17% of heterosexual adolescent students reported having experienced bullying (Kann et al., 2017). This study also indicated that 16% of LGB youths experienced more sexual dating violence by their partners than 6% of heterosexual youths. Additionally, 23% of LGB youth reported suicide attempts, whereas only 5% of heterosexual youths reported suicide attempts (Johns et al., 2020).

LGBTQIA communities are regarded as heterogeneous social groups that have intersecting social identities, including gender identity, ethnicity/race, and sex, among others. They also exude differences when it comes to their risk for suicide and violence. For instance, Johns et al. (2020) reported in their research that LGB females seem to be more likely to engage in risky dating and are vulnerable to sexual violence compared to LGB males. Another study showed differences regarding the risk for suicide and violence among this group. One study that focused on interpersonal violence in sexual minorities stated that intimate partner physical victimization was one to four times more common among youths who were non-whites than youths who were whites (Whitton et al., 2019). A different study also showed that Hispanic LGB and non-Hispanic LGB youths tend to be bullied more than non-Hispanic heterosexual youths (Mueller et al., 2015). This paper contributes to the proof provided by other researchers regarding violence victimization or bullying, LGBTQIA students, and suicide risks. The YRBS data will be used to analyze the national trends in bullying/violence victimization and suicide attempts among school-going youths by sexual identity self-reports and evaluate the differences among LGBTQIA youths by ethnicity/race and sex.

Literature Review

Definition of the Problem

Bullying victimization negatively affects the health of 20% of students, including suicidal behaviors and suicidal thoughts (Lian et al., 2022). This makes bullying victimization a severe public health concern for teenagers in the United States and a high priority for Healthy People 2020 (CDC, 2020). Teenagers who are gender nonconforming or a sexual minority have reported an increased rate of adverse health results, including bullying victimization (Lowry et al., 2018).

Preventing bullying at schools is a fundamental human rights matter, as bullying violates the basic right to education (Lian et al., 2022). Many researchers have found that gender and sexual minority teenagers are vulnerable to experiencing bullying at school (Lian et al., 2022). Many research studies view transgender, bisexual, gay, and lesbian as LGB and T because they see them differently. They argue that LGB is based on sexual orientation, and T is gender identity. Either way, it has been found that transgender teenagers experience considerable disparities in bullying (Day, Perez-Brumer & Russell, 2018).

Few studies have analyzed bullying across the spectrum of gender expression (See –Appendix) (Lian et al., 2022). For instance, a 2013 YRBS showed a linear relationship between gender nonconformity and bullying victimization among high school students in the United States. Gender nonconformity score is linked with a 15% risk increment in cyber or traditional victimization (Gordon et al., 2018). The 2019 YRBS cycle of data collection is the first opportunity to investigate linear trends in bullying victimization and risks of suicide trends for LGB school-going youths across time-based on a nationally representative sample.

Some research studies also suggest that teenagers with nonconforming expressions of gender are also more vulnerable to bullying, victimization, violence, and discrimination (Gordon et al., 2018). A sample from a 2013 study on LGBT students in high school found that 55% of students had been harassed verbally and 11% assaulted physically at school because of gender expression (Gordon et al., 2018).

In addition, bullying has been said to be a public health issue, with a prevalence of 9% to 54% worldwide (Kim & Leventhal, 2008). Kim & Leventhal (2008) argue that all bullying participants are reported to be at high risk for physical and mental sequelae of bullying. They add that victims of bullying face many clinical challenges, such as feelings of insecurity, depression, sleep difficulties, bed-wetting, unhappiness, school phobia, somatic symptoms, isolation, loneliness, and low self-esteem. On the other hand, the perpetrators of bullying have been reported to have depression and tend to show antisocial behaviors as well as legal challenges later in their lives. In 2008, suicide was ranked as the third leading cause of mortality among teenagers in the US and all over the world (Kim & Leventhal, 2008). Not only do the perpetrators of bullying experience psychological problems such as depression, but also the victims of the bullying. This means that suicide affects both the victims and perpetrators. Moreover, in 2008, 19% of adolescents in high schools reported suicide ideation, whereas 15% made particular plans of attempting suicide, and 2.6% of them attempted suicide that required medical intervention (Kim & Leventhal, 2008). In addition, the findings of the 2017 YRBS showed that the LGBTQIA community high school adolescents experienced more bullying than their counterparts.

These data show the urgency for communities to comprehend the connection between bullying victimization and perceived gender expression for the school-going youth of every sexual orientation identity. Some research studies show that sexual minority youth, like LGBT youth, tend to be gender nonconformists (Gordon et al., 2018). Despite this, expression of gender is different from sexual orientation identity, and many heterosexual youths have reported being gender nonconformists. Given the high bullying victimization rate, especially among sexual minorities such as LGBTQIA+ school-aged youth, it is crucial to comprehend the association between bullying victimization and sexual orientation identities in formulating programs that prevent bullying in schools.

Scope, Magnitude of the Problem

Bullying is a considerable risk factor for suicidality among teenagers in the United States. Suicide among the youth was recorded as the fourth leading cause of mortality worldwide in 2004 (Arnarsson et al., 2015). The exact rate of suicide in the LGBTQIA community in the world is still not known because sexual orientation is hardly included in the mortality information (Arnarsson et al., 2015). However, suicide attempts and ideations can be traced and are viewed as crucial predictor aspects for adolescent suicide. Research evidence shows that cyberbullying is connected to suicidality more than physical or traditional school bullying (Van Geel et al., 2014). According to Levine et al. (2022), this is because of the insidious nature of electronic bullying compared to traditional bullying; cyberbullying perpetrators get anonymity and can access a more vast audience without fearing the repercussions of bullying. Besides, electronic data can hardly be recalled once released. Levine et al. (2022) also found that suicide is the second major cause of adolescent death in the US. This is because of the increased rate of cyberbullying, which skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the increased online presence of adolescents (Levine et al., 2022).

One research study has indicated that 80 to 91% of LGBTQIA students self-reported being victims of verbal harassment and name-calling in the school environment and that at least 40% were harassed physically (Kosciw et al., 2012). Since adolescents are characterized as a social group with high sensitivity to their peers (Mueller et al., 2015), this kind of harassment can be distressing to them. Whether the harassment happens in the physical environment or online, it does not limit the negative impacts that bullying has on adolescents’ wellbeing and mental health (Schneider et al., 2012). Mueller et al. (2015) reported that youths who have experienced harassment or bullying tend to report depression, delinquent behaviors, poor academic performance, low self-esteem, and higher levels of drug use and alcohol consumption. They added that youths who reported their experience of being bullied or harassed also had a higher rate of suicide ideation and suicide attempts.

Even though LGBTQIA youths have increasingly reported bullying in the US, there are crucial factors to consider, such as gender, ethnicity/race. Previous research studies have shown that male youths are more likely to report their experiences of being bullied than their female counterparts (Mueller et al., 2015). Moreover, White adolescents tend to report being bullied more than Black youths (Mueller et al., 2015). However, these research studies are not conclusive in providing proof of the ethnic differences in bullying. Few studies have supplied evidence of this. For example, the 2011 Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network survey of national schools discovered that Black LGBTQIA students were less likely to feel unsafe when they were at school. The survey also revealed that they report verbal or physical harassment because of their sexual orientation more than their multiracial, Hispanic, and White LGBTQIA peers (Kosciw et al., 2012). This research also found that Black LGBTQIA youths were less likely to be bullied based on their sexual orientation than their white LGBTQIA counterparts. Experiences of bullying at school were reported as follows: Blacks-54%, Whites-65%, and Hispanics- 62% (Mueller et al., 2015). Moreover, the recent YRBS data showed that Hispanic and White LGBTQIA youths missed school because they did not feel safe compared to their heterosexual peers. However, this does not undermine the reported cases of victimization among other ethnicities like Asian and Black school-going youths.

Problem Etiology and Theoretical Understanding

More research has shown the theoretical link between bullying and suicide ideation and attempts. For instance, the association between cyberbullying victimization and suicidality is empirically supported and theoretically supported. According to the interpersonal school of thought, suicidality results from feeling like the individual does not belong and is a burden to others, leading to a hopeless feeling, which ultimately results in suicidal thoughts (Chu et al., 2017). Based on this theory, research studies have shown that cyberbullying victimization can present solidly to teenagers feeling this way, leading to depression and, subsequently, suicidality (Litwiller & Brausch, 2013). Litwiller & Brausch (2013) also found that this connection showed that violent behaviors and substance use could influence this link among teenagers.

According to Levine et al. (2022), cyberbullying victimization for female youth is more often than not in the form of cyber-sexual harassment. According to the 2019 YRBS data, 17% of adolescent female students, as opposed to 5% of males, reported sexual violence and instances of being physically forced to touch, kiss, and engage in sexual intercourse without consent (Basile et al., 2020). The representative data nationally of US high school students also showed higher odds of connection between sexual violence and suicidal ideation for girls than boys (Baiden et al., 2020). The findings of Baiden et al. (2020) concluded that the interaction between sexual violence and cyberbullying might influence suicidality, and these outcomes may be different based on the gender of the respondent.

Concerning males, sexual orientation is a matter of concern more than it is for females. Levine et al. (2022) wrote that transphobic and homophobic bullying affects males and females disproportionately and even more for bisexual, lesbian, and gay individuals. More often than not, transphobic and homophobic bullying is perpetrated by males. Tucker et al. (2016) argued that the male perpetrators do this because they want to reinforce the traditional norms of gender, exert control, and humiliate the ‘abnormal.’ Levine et al. (2022) find that this bullying, whether electronically or physically, is linked with higher psychological distress, such as suicidality and depression. This may lead to the hypothesis that cyberbullying victimization is higher among girls; it is a solid risk factor for suicidality among boys since cyberbullying is often aimed at sexual orientation.

Moreover, Chiu & Vargo (2022) find that the factors that cause suicidal ideation and attempts of suicide are complicated. A research study found that suicide behaviors result from various biological interplays, including age and gender, psychological aspects such as loneliness, anxiety, and depression, and social-environmental factors like bullying, sexual abuse, and family abuse (Chiu & Vargo, 2022). Freeman et al. (2017) discovered that biological factors like age and gender are linked to suicidal behavior. They added that gender was the critical aspect affecting mental health and suicide among teenagers. In Miranda-Mendizabal et al.’s research (2019), females between the ages of 12 and 26 were reported to be more likely to make suicide attempts than their male counterparts. Since most teenagers find their identities linked to their biological and environmental factors, they tend to associate with a specific identity they relate to. For example, Adelson (2012) theorized that male homosexuality was caused by overly distant fathers or hostile fathers and extremely close mothers. Children of such families are said to grow up and distance themselves from the opposite sex that was absent or hostile to them. It is, therefore, a form of deviant behavior. During adolescence, when adolescents try to discover their identities, they mainly associate with the general population with whom they share similar characteristics. Upon realization that other adolescents may not conform to the norm, bullying perpetrators find the confidence to ensure that the nonconformists feel bad about their choice of gender or identity, in this case, LGBTQIA. Due to their failure to adhere to the normalcy of society, sexual, gender, and tolerance, minority youth become susceptible to bullying, harassment, ostracism, criticism, or rejection by their families and peers, even in the reasonably tolerant, cosmopolitan environment (Berlan et al., 2010).

In another research study conducted in the Philippines, bullying was found to be an independent factor that predicted suicide attempts and suicide ideation in both female and male adolescents (Chiu & Vargo, 2022). The study found that bullying was a key predictor of suicidal behavior, especially in the Filipino cohort. Still, it was not a decisive factor like lack of social networking and loneliness. The research discovered that risk factors linked to lack of social network and loneliness were more vital indications of suicidal behaviors among school-going adolescents than bullying. However, bullying was linked to driving adolescents to those risk factors. Chiu & Vargo (2022) explained that victims of bullying were progressively ostracized, leading to their decreased social competencies as well as lower self-esteem. This led to the conclusion that victims of bullying tend to be continuously bullied and excluded socially from school, class, community, and friendship and with reduced or no support from peers. This loneliness and social isolation are what drive them to suicidal thoughts and attempts.

More often than not, victims of bullying who get bullied constantly and are isolated from their peers are prone to mental health issues lon, loneliness, and, as a result, suicidal behaviors. Chiu & Vargo (2022) find that peers who see victims bullied tend to do nothing even though they understand that bullying is wrong because their concern is security and acceptance in the peer community. Besides, peers who defend victims of bullying are likely to be targets of bullying themselves, which would increase their possibility of isolation from their peers and friend groups at school (Chiu & Vargo, 2022). They may then end up like the other bullying victims.

In sum, adolescence is a phase where teenagers want to feel a sense of belonging. Various reasons, such as genetics, social/parental detachment or over-closeness, and environmental factors, may cause some adolescents to be inclined to a particular identity or behavior that society considers deviant. As a result, they face hostile treatment from the rest of the general population, who feel the minority are different from them and have nothing to associate with or in common.

Proposed Solutions

In a society with increased reported cases of mental health issues, there is a need to understand the connection between mental health and peer behaviors to formulate effective intervention and prevention strategies for school-aged children. The increased use of digital technology has already given rise to the increased use of technological devices among adolescents, including harmful use such as cyberbullying.

This research paper proposes a development or contribution to practice and policy focused on minimizing cyberbullying and bullying and creating a safe learning environment for LGBTQIA+ students. An additional contribution would be that teen victims of bullying need to be screened for suicidality and depression to better provide support in dealing with trauma to reduce mental health risks. The providers of such programs need to be constantly aware of how victimization, such as sexual violence, can exacerbate mental health risks, especially in male youth.

Research Questions/Hypothesis

Based on these findings, including the YRBS data, males are more likely to experience bullying based on sexual orientation at school and even electronically than females. Therefore, they are more at risk for suicidality than females in school-aged children. To analyze the YRBS data further, this research study is guided with more questions, such as:

- To what extent do bullying victimization and trends of suicide risk differ from the trends among heterosexual school-going adolescents in 2015, 2017, and 2019?

- To what level do bullying and suicidality risk trends differ based on ethnicity/race? That is among Hispanic, White, and African American students.

- How do bullying and suicide risk trends vary among female and male students?

- What was the prevalence of bullying and suicide attempts among the vulnerable student community (LGBTQIA+) between the years 2015 and 2019?

Innovation Section

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) argues that sexual minority youths are at an increased risk for particular adverse health outcomes. Youth who identify as gay, lesbian, and bisexual report high levels of violence, substance use, victimization, and suicide risk compared to their heterosexual peers. According to data collected between 2015 and 2017 by the CDC, results show that in comparison to heterosexual students, LGBTQIA+ youth report more alcohol and drug use, victimization, and suicide risk (Johns et al., 2018). The CDC recommends support programs to reduce suicide risk, substance use, and victimization among sexual minority youths. This article will be helpful in this research as it provides information on victimization experiences among sexual minorities and offers additional information on factors such as suicide risk and substance use, which are common among this population.

Kosciw and Palmer (2014) claim that coming out is a crucial milestone among LGBTQIA+ youth, but it also makes them more vulnerable to peer victimization. The authors focus on the connection between LGBTQIAs’ outness regarding their sexuality and academic and psychological outcomes. They claim that harassment in school is likely to interfere with LGBTQIA+ youths’ psychological wellbeing, connection to the school community, and educational achievement. This article will benefit this research as it provides crucial information on the link between victimization and suicidal ideations among LGBTQIA+ youth. In particular, the authors claim that the opposing school experiences of LGBTQIA+ youth predispose them to worse mental health outcomes compared to their non-LGBTQ peers and put them at an increased risk for suicidal behavior ide, action, and risky sexual behaviors. This article also recommends a resilience framework to help LGBTQIA+ youth navigate various problems they might face in school.

Similar to the CDC and Kosciw and Palmer’s findings, Williams, Banks, and Blake (2018) argue that sexual minority youths are more likely to experience bullying and adverse outcomes from bullying than their heterosexual peers. The authors refer to this kind of bullying as bias-based bullying, which includes any form of bullying behavior directed at the perceived or actual sexual orientation and expression towards a target student. In their research, Williams et al. (2018) claim that most participants claim to be verbally abused in school due to their sexual orientation, and a few others claim to be physically harassed. It is found that this type of bias-based bullying results in poorer ratings regarding school connection, increased rates of dropout, and increased suicidal attempts. This article will also be necessary for this research as it identifies a strong link between what is referred to as bias-based bullying and suicidal attempts. The report also offers recommendations for lessening bullying rates in school by identifying the role that bystanders can play when one is being bullied for one’s sexual orientation.

Johns et al. (2020) also support the claim that more LGBTQ youths in school experience more suicide risk and violence victimization than heterosexual peers. This article shows that 33 percent of sexual minority students in school experience bullying compared to only 17 percent of heterosexual peers and 23 percent of suicide attempts compared to only five percent among heterosexuals. This article shows a strong link between bullying and suicide risk among sexual minority youths and will benefit this research. The authors claim that female sexual minorities have higher rates of suicide risk behaviors and tendencies compared to LGBTQ males. However, they also report that more sexual minority male youths die from suicide than their female counterparts.

Jadva et al. (2021) also claim that LGBTQ youth have a heightened risk of suicide, suicidal attempts, and self-harm than their heterosexual and cisgender peers. The article claims that 84 percent of trans youths report suicidal ideations, and 48 percent report attempted suicide. Similar to the CDC’s findings, Jadva et al. (2021) argue that stress, discrimination, prejudice, and stigma linked to sexual minorities are accountable for increased mental health problems among sexual minorities. In their research, the authors claim that most sexual minority youths experienced higher suicidal ideation, self-harm, and suicide attempts. Bullying was considered the primary trigger behind these suicidal tendencies. This article will also benefit this research, providing critical information on the link between bullying and suicide rates among sexual minority youths. The authors claim that sexual minority students who had been bullied were 2.6 times more likely to attempt suicide and 2.2 times more likely to undergo suicidal ideation than their heterosexual peers.

Also, this research will build on the scarce evidence that previous research studies have provided on the differences in bullying among genders and ethnicities/races. Lastly, Goodboy and Martin (2018) also claim that even though every youth is vulnerable to bullying, specific populations are at increased risk compared to others. In their research, they are a sexual minority predisposed individuals to more bullying tendencies. The authors write about various personal experiences of individuals who identify as LGBTQ. Most of them claim to have indulged in self-harm, suicidal attempts, or ideations due to some form of bullying, including physical, verbal, or online. Bullying causes minority students to experience an adverse school environment, negatively affecting their mental health and general wellbeing. This article will also help provide crucial supporting information, showing a strong link between bullying and suicidal tendencies.

Research Methodology

Measurement

This study will use the YRBS of 2015, 2017, and 2019 about students who responded to questions about violence victimization. These studies include those who have experienced coerced sexual intercourse, physical dating violence, sexual dating violence, electronic bullying, bullying at school, sexual dating violence, and those who have been injured or threatened with a weapon at their schools in the previous year. Those students who report missing school due to feeling unsafe while at school will also be evaluated. Other measures will be based on students who will respond to suicide risks in the past year, including those who will answer the question about feeling persistently hopeless and sad, those who have considered suicide seriously, those who have attempted suicide, and those who made plans for committing suicide. Demographic variables, including ethnicity, race, grade, sexual identity, and sex, will also be measured.

The students who report experiencing bullying through verbal, assault, or sexual harassment will be assessed within the last year. This data will be measured as verbal, physical, and sexual. Verbal harassment includes whether the participant has been threatened verbally or is a victim of name-calling. The physical assessment will evaluate whether the respondent has been battered with a weapon, punched, or shoved. Lastly, the sexual evaluation will show whether the respondent has been forced to engage in unwanted sexual activity, has received sexual messages or sexual remarks, or has been touched inappropriately. The response choices will be no or yes and under the choice list of assault, sexual harassment, physical, or verbal in the last year based on gender identity or sexuality.

The variable of school experience will also be measured when the respondents were asked how they rated their schools regarding their connection to them. For instance, if they felt like they were part of their school community on a scale of 1 to 5, where one strongly disagreed, and five strongly agreed, and if they felt safe expressing their LGBTQIA+ identity at their learning institutions.

Dataset

This methodology entails data from 2019, which was 13,677; from 2017, which was 14,765; from 2015, which was 15,624; and from the YRBS national cycles. The total was n=44,155. This was a survey that has been carried out biennially since 1991. CDC collects data annually from a representative sample of private and public school students between grades 9 and 12 in fifty states in the US and the District of Columbia. Sampling regarding the YRBS sampling, processing, response rates, and data collection is further explained by Underwood et al. (2020). The estimates of the prevalence for all the questions of suicide risk and victimization for the study population and by ethnicity/race, sex, sexual orientation, questionnaire, and grade are provided by the CDC (2019).

Target Population and Sampling

The group of interest is a group of students in 50 public and private schools in Columbia from grades 9 to 12. At least one of the students from grades 9 to 12 is used in the sampling frame. The 2019 YRBS sampling frame is used in this research. It entails regular public, nonpublic, and parochial schools with students from grades 9 to 12 in the Columbia district. Other schools, such as schools under the US Department of Defense, vocational schools, and schools under the Bureau of Indian Education, were not included in the study sample. Also, schools with 40 or fewer students within the stated grades were excluded. The sampling frame was gathered from data sets from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and Market Data Retrieval, Inc. This data was derived explicitly from https://nces.ed.gov/ccd and https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pss.

The level three cluster sampling design was used for this survey to create a representative sample of students from grades 9 to 12 in private and public schools. The first phase sampling frame entailed 1257 sampling units, classified into 16 strata according to the metropolitan statistical place status, including rural and urban areas. The classification was also based on percentages of Hispanic and non-Hispanic/Black students. Out of the 1257 primary sampling units, probability proportion was used to sample 54. In the second sampling phase, double units were identified as physical schools having grades 9 to 12 or a school that is established by joining neighboring schools to provide the four grades. Out of the 54 primary sampling units, there were 162 secondary sampling units using probability proportional to the school enrollment size. More than 15 small secondary sampling units were chosen from a subsample of the 15 primary sampling units from the 54 direct sampling units. The total 177 secondary sampling units corresponded with the 184 physical schools in the district. In the third sampling phase, random sampling was used to select one or two classrooms from either Social Studies or English in every 9 to 12 grades. All students in the classrooms were considered eligible to participate in the survey. Students, classes, and schools that refused to participate in the study were not replaced in the sampling design. This was respected. All students signed a non-disclosure agreement, and those who were hesitant to participate were not forced.

Research Design

For this research methodology, the plan is to focus on LGBTQ youth. We plan to utilize data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC has identified data relating to LGBTQ youth experiencing violence at school. In addition, this data also identifies the effect this violence has on the youth’s mental and emotional health. This data will be the basis of the research methodology.

As the research question is aimed at understanding the relationship between bullying based on sexual orientation and suicide attempts, we must recognize that our population is considered vulnerable participants. This means we are looking at how something would affect individuals previously identified as a vulnerable population. The Office for Human Research Protections includes pregnant women and fetuses, minors, prisoners, persons with diminished mental capacity, and educationally disadvantaged persons, a vulnerable population (HHS.gov).

The research design will use stratified and clustered sampling, such that when data is weighted, it represents the US population of high school students. Notably, there is so much skepticism regarding self-reported cases of bullying victimization by school-aged youths and suicidality. Nonetheless, the CDC modifies and develops questions inputted by the information experts every two years and has also documented the reliability of school-aged youths’ responses to the generated questions. Moreover, data between 2015 and 2019 will be used since this timeframe overlaps with more states that asked sexual identity questions and a few states that had implemented anti-bullying policies in the previous years.

Sample

The sample data will be filtered to include unintentional injuries and violence and racial/ethnic groups, including Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. This is because Whites are the most dominant population in the US, and compare that data with minority ethnic groups such as Blacks and Hispanics. All sexual orientations will also be included in the sample. The respondents who select being bullied on the school property and those who have experienced cyberbullying will be studied.

Ethics

The study considered the protection of the research participants by not disclosing their names and by adhering to the school’s protective practices, such as involving supportive school personnel and a curriculum that entails LGBTQ events or figures and safe spaces. The study ensured that all participants consented to participate. The parents and guardians were contacted to provide. They also agreed to their children’s participation in the study. Laws and policies supporting the LGBTQ youth against further bullying were also implemented to ensure that participants are further protected from electronic and physical bullying and victimization even after participating in the study. The study confirmed that whistleblowing measures were in place so that the LGBTQ youth had a safe platform to report cases of bullying or victimization related to their participation in the study.

The CDC database also protects participants’ identities because all data in the YRBSS are self-reported. The participants also go through screening questions for participation eligibility, which means an agreement is achieved before collecting data from the vulnerable population. Besides, YRBSS data is made available for the whole US, some local school districts, some territories, most states, and some tribal governments.

In addition, the data obtained in YRBSS have followed the reliability and validity guidelines where internal reliability checks are made to assist in identifying the minimal percentage of respondents who falsify their answers (CDC, 2022). All participants have been assured that their anonymity and privacy have been protected. For instance, according to the CDC (2022), test-retest reliability studies were done between 1991 and 1999, where the validity of self-reporting, among other variables, was tested.

Critique: Limitations and Challenges

Some limitations of our research include insufficient resources and the small sample size. This is because the sample population is considered vulnerable, which limits what we can do regarding research. Therefore, we are relying on preexisting data to conduct our research. This could cause a somewhat limited view of our research and not allow us to look into other perspectives. Since all data in the CDC are self-reported, the chances of under-reporting are high (CDC, 2022). This means the study must gather information from various years to have sufficient information.

Moreover, data derived from YRBS is focused only on youths who attend school. Consequently, this does not represent every person who is an adolescent. This limitation is also a strength of this research study since the study focuses on school-going students. However, its limitation is based on the fact that 5% of high school-aged adolescents between the ages of 14 and 17 did not enroll in school in 2019 (US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). According to Underwood et al. (2020), youths not enrolled in high school may be riskier than their peers, and such behaviors are not entailed in the school-based YRBS.

Also, it is difficult to determine the extent of over-reporting and under-reporting of health-based behaviors, such as bullying and suicide attempts, even though the survey questions have demonstrated better retest and test reliability (Underwood et al., 2020). Also, since not all local school districts and states present the standard questions needed for the YRBS data, some variables may not be available on the site. According to Johns et al. (2020), the YRBS is based on data analyses that are cross-section surveyed, which gives only an indication of the relationship as opposed to causality. Therefore, one cannot be 100% sure that the cause of suicide attempts and ideation is bullying victimization.

Additionally, the YRBS data is mainly descriptive and, therefore, can hardly explain the reason for any observed trends. Besides, since adolescence is a phase of self-discovery, some respondents may not be fully aware of their sexual orientation when the surveys were administered. This is why using data from 2015 to 2019 was necessary for this study because it increases the chances of getting the required sample. According to Johns et al. (2020), youths who report or choose the selection of unsure about their sexual orientation are those who are uncertain about their sexual identity and did not comprehend the question or were not comfortable answering it. This category may choose this selection for various reasons, including bullying-related trauma. Therefore, using data that excludes some groups that should be included in the study proves to be a limitation of this study.

Results

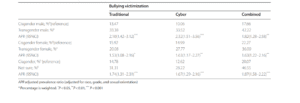

Violence Victimization

Among the participants, LGB youths showed higher odds of violence victimization compared to heterosexual students across the indicators, including coerced sexual intercourse, sexual dating violence, physical dating violence, online bullying, bullying at school, injured/threatened with a weapon in the school environment, and unsafe feeling at school. Among the LGB youths, there was a percentage decrease in those who reported physical dating violence experience from 17.5% to 13.1% (CDC, 2020).

Additionally, male youths reported feeling unsafe at school and on their way to or from school, as well as being injured/threatened with a weapon more than the female youths. The results also showed male LGB youths reporting reduced rates of online bullying, coerced sex, and sexual dating violence than their female counterparts. Male students who reported injury/threat by a weapon increased from 2015 to 2019 from 11.6% to 15.9%, and those who experienced coerced sex increased from 8% to 15.6% (CDC, 2020). On the other hand, female students reporting physical violence reduced from 2015 to 2019 from 16.9% to 12.1% (CDC, 2020).

The results also showed Black and Hispanic LGB youths at higher odds of unsafe feelings at school than White LGB youth. Most Black students also reported being threatened with a weapon or injured more than Whites. They also reported reduced sexual dating violence compared to white LGB youth. The most notable trend was violence data among Hispanic LGB youths, which had decreased tremendously from 22.6% in 2015 to 9.8% in 2019 (CDC, 2022).

Risk of Suicide

All LGB youths in the sample showed a greater risk of suicide than the heterosexual LGB youths based on the indicators of making a suicide plan. This suicide attempt needed medical intervention, persistent hopelessness/sadness feelings, seriously considering suicide, and attempted suicide. The rate of LGB youths that reported these results did not vary much from 2015 to 2019. Concerning sex, male LGB students showed lower odds in the suicide risk indicators than female students. Regarding female LGB students, the rate of suicide attempts reduced considerably from 32.8% in 2015 to 23.6% in 2019, but other trends in the risk of suicide stayed more or less the same (CDC, 2020).

The LGB students who were classified based on ethnicity/race data showed that Hispanic and Black LGB students were at lower odds than their White counterparts regarding persistent hopelessness/sadness feelings and seriously considering suicide. On the other hand, Black LGB students had lower odds of plotting a suicide plan than their White counterparts. These reports did not vary much between 2015 and 2019.

Discussion

According to the CDC YRBS results, as indicated above, it is highlighted that there is a high prevalence of bullying and victim victimization among school-going adolescents, which progressively leads them to suicidal behavior compared to heterosexual school-going youths. The high rate of violent victimization and suicidal behavior among the LGB community coincides with the research findings on minority stress and sexual minorities conducted by Meyer & Frost (2013). They found out that minority stress lays the grounds for comprehending sexual minority disparities. It is the process by which stigmatization towards LGB and other non-heterosexual individuals is enacted via external factors such as harassment, discrimination, violence, and violence, as well as internal factors like expectations of rejection. Therefore, these results underscore the importance of minority stress among LGBTQIA adolescents and the urgent action that would address the disparities.

In addition, the fact that fewer LGB youths reported going through physical violence in dating in 2019 compared to 2015 shows a promising decrease in LGB experience in physical dating violence. The reasonably stable suicide risk trend from 2015 to 2019 indicates that LGB students are still experiencing suicide risks at school, probably from other factors aside from physical dating violence.

Furthermore, as shown in the results, more LGB male students reported feelings of insecurity and experiencing threats with a weapon at school than female LGB students. On the other hand, more LGB female students tend to report electronic bullying at school compared to male LGB students. These results agree with Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen, & Brick’s (2010) research findings that males are more likely to report physical harassment and bullying than females and that females are more likely to register online and verbal bullying. It is also evident from the results that females are constantly disproportionately influenced by various kinds of victimization. This is from the result that female students showed a greater rate of sexual dating violence experience and coerced sex than male students. Overall, both female and male LGB students are influenced negatively by violence. However, these results show an increased prevalence of violence among male students more than females.

Also, this data showed that LGB female students experienced decreased suicide attempts from 2015 to 2019. However, female LGB students constantly reported suicide risk behaviors more than male LGB. This may explain why males experience more suicide mortality than females because their experiences may go unnoticed until death. This data calls for more research on how LGB students are affected by suicide risk behaviors to lead to the best practices for addressing the problem.

Lastly, as seen from the data, Hispanic and Black LGB youths reported feelings of insecurity and experiences of injuries and threats with a weapon more than White LGB youths. This shows that Hispanic and Black LGB+ students are more vulnerable to forms of victimization based on physical safety than their White counterparts. Besides, White LGB students tend to report electronic and school bullying, which means they are susceptible to social and verbal victimization. These results indicate that there are differences by ethnicity/race among sexual minorities. Therefore, interventions must consider these differences when implementing measures to address bullying at school.

Regarding the risk of suicide, a lower rate of Hispanic and Black LGB students reported hopelessness, sad feelings, and suicide contemplation than White LGB students. However, there were no differences among the ethnicities/races regarding suicide attempts and medically severe attempts of suicide. This shows that all LGB students are vulnerable to suicide, irrespective of ethnicity/race, and this underscores the impact of minority stress on mental health among all ethnic/racial populations.

Conclusion

The CDC YRBS seems to be the best resource for quality data on local school, tribal, territorial, state, and national levels for examining health-related youth behaviors. These behaviors contribute to the leading causes of morbidity and mortality rates among high school students in the US, which can result in health issues during adulthood. Using this source to determine youth’s increased problems, especially at school, will help contribute to societal practice and policy changes. For instance, previous research studies have shown an urgent need for school practices and policies to minimize bullying victimization and enhance mental health, especially for vulnerable youths such as LGBTQIA+ students. Schools may consider engaging with the stakeholders and community-based organizations to implement effective suicide and violence prevention mechanisms that address protective and risk factors at societal, community, relationship, and individual levels. This research will help in refining practices and policies that prevent suicide and support victims to include the needs of vulnerable populations like LGBTQIA+ youths. Therefore, this research will expectantly help to monitor the disparities between bullying and suicide attempts and ideation among heterosexual youth and LGBTQIA+ youths until they are eradicated.

Besides, from the CDC YRBS, there is a continued need for best practices and policies in schools to minimize bullying and victimization and enhance mental health among minority groups such as LGB+. Schools should embrace policies and programs that strengthen staff support for all students and anti-harassment (Johns et al., 2019). The schools can also consider partnering with stakeholders and organizations in the community to collaborate in implementing comprehensive suicide and violence prevention approaches that would address various risk factors at societal, community, relationship, and individual levels. For instance, comprehensive mechanisms to minimize suicide assist in preventing suicide risks, offer support to vulnerable individuals, prevent re-attempts, and help victims of suicide.

References

Adelson, S. L. (2012). Practice parameters on gay, lesbian, or bisexual sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and gender discordance in children and adolescents. Journal of the American academy of child & adolescent psychiatry, 51(9), 957-974.

Arnarsson, A., Sveinbjornsdottir, S., Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Bjarnason, T. (2015). Suicidal risk and sexual orientation in adolescence: A population-based study in Iceland. Scandinavian journal of public health, 43(5), 497-505.

Baiden, X., Y., Asiedua-Baiden, G., LaBrenz, C. A., Boateng, G. O., Graaf, G., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2020). Sex differences in the association between sexual violence victimization and suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 1, 100011–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100011

Basile, C., H. B., DeGue, S., Gilford, J. W., Vagi, K. J., Suarez, N. A., Zwald, M. L., & Lowry, R. (2020). Interpersonal Violence Victimization Among High School Students – Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Supplement, 69(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a4

Berlan, E. D., Corliss, H. L., Field, A. E., Goodman, E., & Austin, S. B. (2010). Sexual orientation and bullying among adolescents in the growing up today study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(4), 366-371.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F. A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth violence and juvenile justice, 8(4), 332-350.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). LGBT Youth. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/youth.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2019/2019_YRBS-National-HS-Questionnaire.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Healthy people -2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 31, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). YRBSS. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Adolescent and School Health. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/faq.htm

Chiu, H., & Vargo, E. J. (2022). Bullying and other risk factors related to adolescent suicidal behaviors in the Philippines: a look into the 2011 GSHS Survey. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1-12.

Chu, C., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Tucker, R. P., Hagan, C. R., Joiner, T. E. (2017). The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of a Decade of Cross-National Research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123

Day, J. K., Perez-Brumer, A., & Russell, S. T. (2018). Safe Schools? Transgender Youth’s School Experiences and Perceptions of School Climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1731–1742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0866-x

Freeman, A., Mergl, R., Kohls, E., Székely, A., Gusmao, R., Arensman, E. & Rummel-Kluge, C. (2017). A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 1-11.

Goodboy, A. K., & Martin, M. M. (2018). LGBT bullying in school: perspectives on prevention. Communication Education, 67(4), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2018.1494846

Gordon, A. R., Conron, K. J., Calzo, J. P., White, M. T., Reisner, S. L., & Austin, S. B. (2018). Gender Expression, Violence, and Bullying Victimization: Findings From Probability Samples of High School Students in 4 US School Districts. The Journal of School Health, 88(4), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12606

HHS.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/45-cfr-46/index.html#:~:text=The%20HHS%20regulations%2C%2045%20CFR,D%2C%20additional%20protections%20for%20children.

Jadva, G., A., Bradlow, J. H., Bower-Brown, S., & Foley, S. (2021). Predictors of self-harm and suicide in LGBT youth: The role of gender, socio-economic status, bullying, and school experience. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England). https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab383

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Rasberry, C. N., Robin, L., Scales, L., Suarez, N. A. (2020). Trends in violence victimization and suicide risk by sexual identity among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2015–2019. MMWR supplements, 69(1), 19.

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Rasberry, C. N., Dunville, R., Robin, L., Pampati, S., Kollar, L. M. M. (2018). Violence victimization, substance use, and suicide risk among sexual minority high school students—the United States, 2015–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(43), 1211.

Johns, M. M., Poteat, V. P., Horn, S. S., & Kosciw, J. (2019). Strengthening our schools to promote resilience and health among LGBTQ youth: Emerging evidence and research priorities from the state of LGBTQ youth health and wellbeing symposium. LGBT health, 6(4), 146-155.

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Ethier, K. A. (2017). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

Kim, Y. S., & Leventhal, B. (2008). Bullying and suicide. A review. International journal of adolescent medicine and health, 20(2), 133-154.

Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Bartkiewicz, M. J., Boesen, M. J., & Palmer, N. A. (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). 121 West 27th Street, Suite 804, New York, NY 10001.

Kosciw, Palmer, N. A., & Kull, R. M. (2014). Reflecting Resiliency: Openness About Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Its Relationship to Wellbeing and Educational Outcomes for LGBT Students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1-2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6

Levine, R. S., Bintliff, A. V., & Raj, A. (2022). Gendered Analysis of Cyberbullying Victimization and Its Associations with Suicidality: Findings from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Adolescents, 2(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents2020019

Lian, Q., Li, R., Liu, Z., Li, X., Su, Q., & Zheng, D. (2022). Associations of nonconforming gender expression and gender identity with bullying victimization: an analysis of the 2017 youth risk behavior survey. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 650–650. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13071-6

Litwiller, B. J., & Brausch, A. M. (2013). Cyber Bullying and Physical Bullying in Adolescent Suicide: The Role of Violent Behavior and Substance Use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9925-5

Lowry, R., Johns, M. M., Gordon, A. R., Austin, S. B., Robin, L. E., & Kann, L. K. (2018). Nonconforming Gender Expression and Associated Mental Distress and Substance Use Among High School Students. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1020–1028. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2140

Meyer, I. H., & Frost, D. M. (2013). Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. New York: Oxford University Press.

Miranda-Mendizabal, A., Castellví, P., Parés-Badell, O., Alayo, I., Almenara, J., Alonso, I. & Alonso, J. (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. International journal of public health, 64(2), 265-283.

Mueller, A. S., James, W., Abrutyn, S., & Levin, M. L. (2015). Suicide ideation and bullying among US adolescents: Examining the intersections of sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity. American journal of public health, 105(5), 980-985.

Russell, S., & Osher, J. (2001.). Sex ed for social change. Siecus. Retrieved July 28, 2022, from https://siecus.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/29-4.pdf

Schneider, S. K., O’Donnell, L., Stueve, A., & Coulter, R. W. (2012). Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. American journal of public health, 102(1), 171-177.

Shields, J. P., Whitaker, K., Glassman, J., Franks, H. M., & Howard, K. (2012). Impact of Victimization on Risk of Suicide Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual High School Students in San Francisco. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(4), 418–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.009

Tucker, J. S., Ewing, B. A., Espelage, D. L., Green, H. D., de la Haye, K., & Pollard, M. S. (2016). Longitudinal Associations of Homophobic Name-Calling Victimization With Psychological Distress and Alcohol Use During Adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(1), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.018

Underwood, J. M., Brener, N., Thornton, J., Harris, W. A., Bryan, L. N., Shanklin, S. L., Dittus, P. (2020). Overview and Methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System – United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Supplement, 69(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a1

US Department of Education. (2019). Fast facts: enrollment trends. National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: US Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=65

Van Geel, M., Vedder, P., & Tanilon, J. (2014). Relationship Between Peer Victimization, Cyberbullying, and Suicide in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(5), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143

Whitton, S. W., Newcomb, M. E., Messinger, A. M., Byck, G., & Mustanski, B. (2019). A longitudinal study of IPV victimization among sexual minority youth. Journal of interpersonal violence, 34(5), 912-945.

Williams, A., Banks, C. S., & Blake, J. J. (2018). High school bystanders’ motivation and response during bias‐based bullying. Psychology in the Schools, 55(10), 1259–1273. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22186

Appendix

Associations between Gender Identity and Bullying Victimization (Lian et al., 2022)

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Purpose of Assignment: The purpose of this assignment is for students to demonstrate their ability to apply research principles to the development of each stage of the research process, including the research question(s), measurement, study design, sampling, data collection, and analysis and reporting of results. Members of each research team will work collaboratively to submit a completed paper that approximates a published research study in tone and style.

Bullying of LGBTQIA Youths vs Heterosexual Youths

As previously mentioned, this is a research team assignment; however, there are certain sections that students must complete individually. Students should complete the individual sections and insert them into their final paper. The following table describes the distribution of work for the final paper.

Submitted papers should include a title page, abstract, body, and reference page. Any additional materials (e.g., a copy of the instrument or a letter documenting approval to conduct the project) should be included in an appendix.

Directions: Each student will submit a paper of 17-20 pages in length (not including appendices, reference, or title pages) that contains the following sections:

- Title Page: Should conform to APA guidelines. Hint: your title should frame your project and contain the variable(s) or concept of interest.

- Abstract

- Introduction

In no more than one page, state your research problem/challenge/concept, the purpose of your research, and its relevance to social work. This section should provide a brief foundation for your paper.

- Literature Review

This section should describe the issue/concept/problem you will be studying and provide the “background” for your research. This section links theory and practice and should contain at least 12 peer-reviewed articles summarizing previous research in your topic area. This should include conceptual articles (theoretical articles) that relate to the problem and the last empirical research that has been done on this problem. Only articles published in professional journals can be counted towards the 12. Examples include Social Work, Families in Society, Journal of Social Work Education, etc. You may, of course, have additional materials such as textbooks, etc.

- Definition of the problem or description of the problem that the intervention addresses if an evaluation study

- Scope, magnitude, of problem/concept/challenge of interest

- Problem etiology (what causes or is believed to cause the problem, how does the problem/challenge/concept develop)

- Solutions to the problem (what is successful): if you are doing an evaluation study, you may want to include studies that have used similar interventions

- Research question/hypothesis (use your literature review to develop a question and research hypotheses). This question or hypothesis should flow naturally from your work.

- Innovation section. Why is your research necessary? Why is it different from other projects that have been done? In other words, why is this worth doing?

Section E should link your current study to the literature review. This should occur at the end of your literature review before stating your question/hypothesis.

- Methods Section

This section describes what you did to implement your project. It should be detailed enough to allow the reader to implement your project.

Measurement – This section should clearly define the concept or program in measurable terms.

-

- Define the concept(s) in your study or describe the intervention of the program evaluation.

- Describe the instruments you used to measure the concepts/variable(s) in your study. Questions to consider (How was the instrument developed? How is it administered? What type of data does it produce? Is it appropriate for use with your selected population?) Make sure that you discuss the reliability/validity of the instrument(s). If you have a pre-testing plan, consult it.

Target Population and Sampling This section identifies your target population and explains in detail how you constructed your sample from this population.

-

- Identify your target population- what group are you interested in studying?

- What was your sampling frame (if you have one)?

- Provide a detailed description of the sampling you used and the process (are you using probability or non-probability sampling methods? What is the specific name of the sample that you used)

- Specify and justify your sample size- how many people do you expect in your sample, and how was this number determined?

- Ethics – How did you protect the rights of your subjects? Think about issues of privacy, informed consent, voluntary participation, etc.

Research Design- This section should provide a plan for conducting the project.

-

- Indicate the research design that you used

- Justify your research design selection in comparison to other designs

- Provide an implementation timeline/work plan describing how you implemented the design and collected your data. This should be specific so that another researcher could take your paper and conduct the project, if necessary.

- Results —This section should identify the results of your study. It should provide only facts. This is where you report the results from your statistical tests. Please organize this section and report statistics as if you would publish in a peer-reviewed journal. Make sure that you describe your sample before moving on to your primary tests.

- Discussion —This section should provide a clear and relevant discussion of your results and describe why you “got the results that you did.” For example, were your results consistent or inconsistent with past research? Were there methodological issues that could have impacted your results? Note: You must use literature from your literature review to provide context for your results.

- Conclusion—What did you gain from this project? How will this project further social work knowledge/what are the implications for social work macro and micro practice?

Appendix Additional materials

-

- copy of instrument

- a letter documenting approval to conduct the project

- proof of completion of the CITI exam