A Critical Review of the Gender Pay Gap in the UK

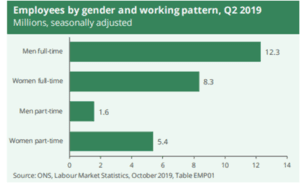

The gender pay gap has remained a contentious issue since women’s venture into the workforce. Despite working for the same number of hours and offering similar outputs as their male counterparts, women receive fewer wages (Brynin, 2017, p. 109). After serving their employers for a significant period, they encounter corporate ceilings, which prevents them from scaling greater heights in their careers. This injustice is prevalent in male-dominated professions such as finance, insurance, and technology, with the gender gap manifesting through the dominance of male workers in management positions (Costa Dias, 2018, p. 5). At the same time, there are more full-time male employees than females.

Trends in the UK’s Gender Pay Gap

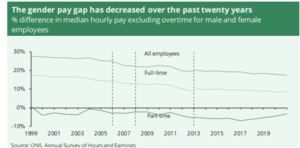

The gender pay gap refers to the difference in hourly wage rates paid out to male and female employees in an organization. Notably, the median hourly wage rates paid out to women were 8.9% less than that of male workers in 2019. On the other hand, the median hourly range issued to part-time female workers was 3.1% more than that offered to male workers in the same year (Apergis, Hayat, and Kadasah, 2019, p. 118). The reason for this discrepancy is there are more female part-time workers than male workers. Notably, the wage disparities between male and female workers feature a downward trend from 1997 to date. Part of the reason for this is the enactment of the Equal Pay Act in 2010, which required employers with a workforce size of more than 250 workers to publish information on unequal pay in their organization (Fortin and Böhm, 2017, p. 110). After the legislation of this bill, reporting was voluntary, but it became mandatory after the enactment of the Small Business, Enterprise, and Employment Act in 2015. These laws have played a significant role in bridging the wage gap between male and female workers.

Moreover, in the past two decades, more women have joined the science, technology, and finance departments through academic qualifications and experience. Another reason for the decline in the gender pay gap is as a result of more women joining the workforce, and the delay of childbirth, awarding women similar opportunities as their male counterparts in the industry (Friedman and Laurison, 2017, p. 480). At the same time, it is essential to note that the gaps in part-time employees remained the same, seeing that this sector employs more part-time female workers than male employees, just like in the past decades.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

The gender pay gap reported in April 2019 was 17.3%, which was considerably higher than the disparities in both part-time and full-time employment combined (O’Neill, 2019, p. 45). This increase was brought about by the wage gap between full time and part-time workers in the UK. In the figure below, the median hourly wage rates among male full-time employees were significantly higher than that of full-time female workers. On the other hand, there were more part-time female workers than male employees

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

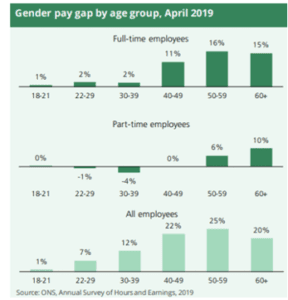

Age Differences

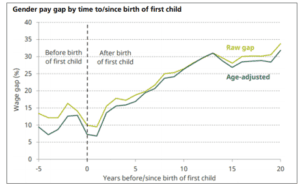

Age is one of the factors contributing to the wage disparity between male and female workers. Notably, the disparity is lowest among young full-time employees and increases with age. It is lowest for the population aged 18-21 and highest for workers aged 60 and above. The reason for the small difference among the young population is the similarity in education levels and years of experience (Jones, Makepeace, and Wass, 2018, p. 296). Female employees in the younger generation have similar, if not higher, academic qualifications than their male colleagues. Also, most of the female employees within this age group have not yet had families and children, and hence are committed to developing their careers. At the same time, this personnel is working at a period when the challenge of unequal pay has not only been widely sensitized but also received government attention seeing the equal pay legislation implemented in 2010 and 2015 (Lips, 2013, p. 170). Hence these female workers are employed at a time when companies are conscious of the issue and have implemented measures to bridge the gap between male and female salaries. On the other hand, the wage gap is more significant among the older populations since the women in this age group are less qualified than their male counterparts for two reasons. Firstly, men exhibit high education levels and years of experience. Secondly, women are disadvantaged due to the hours they spend in rearing their families and sick relatives and hence possess fewer years of experience. According to statistics, the gender disparity between married couples was 10% before raising their young family and escalates to 30% after welcoming their first child (Apergis et al., 2019). Equally important, these responsibilities prevent women from furthering their education, which is required in obtaining full-term competent employment. Studies also indicate that women settle for less paying jobs that demand less of their time so they can focus on tending their families. The wage discrepancies are less significant among young part-time employees since, presently, most companies issue a low rate wage.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

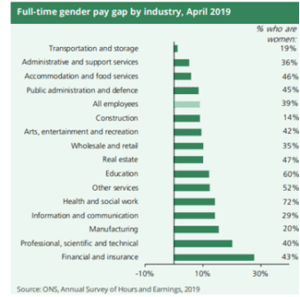

Unequal Pay in Industries

The gap in equal pay is highest in the finance and insurance industry and lowest in transportation and storage, as illustrated in the graph below. This difference is a result of the variation in the number of women contracted in this industry. Notably, finance and insurance, professional, scientific and technical, manufacturing, and information and communication have the most considerable discrepancy (Kentish, 2018, p. 15). The variation in these industries is partly due to the prejudice against women who are considered unsuitable for these job types. Also, these jobs feature full-time employees and are less likely to accommodate women due to maternity leaves as they are considered extravagant labor costs. The discrepancy is lowest in transport and storage, construction, and manufacturing since they mostly offer part-time employment, which features more female employees than male workers.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

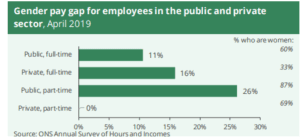

The gender pay gap is more significant in the private sector in comparison to the public sector, as showcased in the below graph. Notably, the proportion of women working full time in the public and private sectors is 60% and 33%, respectively (O’Neill, 2019, p. 46). This variation arises from the state and governmental bodies’ compliance with the directive of issuing the same working opportunities to both female and male employees. At the same time, the public sector is more likely to accommodate female workers since its objective is not profit maximization but serving the public. On the other hand, the for-profits service-based organizations such as finance and insurance, and technology aim to lower labor costs in maximizing profitability.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

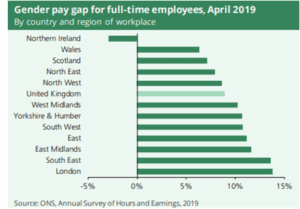

Notably, the gender pay gap varies with regions and is more significant in London and the South East. The wage gap is lowest in Northern Ireland, Wales, and North East, as illustrated in the chart below.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2019 Viewed 13th April 2020

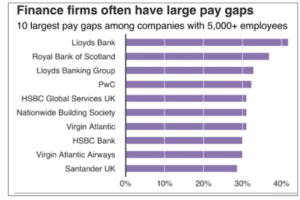

Implications of Unequal Wage Rates

Despite the reduction in gender pay gaps between male and female employees, more companies in the UK uphold the unequal trend through contracting more male workers in management and issuing lower wages to female workers. As a result, these companies are slapped with lawsuits from their female workers, citing unfair pay. In Feb 2019, the female workers in Walmart sued the company for allegedly issuing lower wages to the female workers as opposed to their male counterparts. Some women in middle management positions cited increased job responsibilities under the same wages. Also, they complained of more male workers in management positions. Similarly, BBC employees cited that the top ten most paid employees comprised of male workers. As a result, Carrie Gracie, who works as an editor for the China branch, quit her job, citing discrimination against women in the company (Kentish, 2018, p. 5). Reports from the firm’s workers cited that male international editors earned up to 50% more than their female counterparts, yet they both put in similar efforts. Similarly, Tesco faced a lawsuit from its female employees who cited unequal pay. Lastly, Goldman’s Sachs, which operates in the highly controversial banking and finance sector, was in the limelight after a female employee, Allison Gamba, sued the company for discrimination in their promotion (Costa Dias, 2018, p. 20). Allison stated that despite working tirelessly for a decade, securing a master’s degree and a seat in the New York stock exchange, she was not nominated for the director position. Gamba explained that despite improving the worst-performing stock and her dedication to the firm, she did not secure a chance for the position. Upon consulting her manager, he explained to her that her nomination would make him the laughing stock of his counterparts. Gamba explained that low performing workers were promoted while she retained the same position. The graph below illustrates the wage gaps between male and female workers, with the highest being recorded in the firms operating in the finance sect

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-47252848 Viewed 13th April 2020

Recommendations for Addressing the Unequal Pay Gap in the UK.

Sharing Paternity Responsibilities

One of the proposed approaches to reducing the gender pay gap between male and female workers lies in sharing childcare responsibilities between both parents. According to the report, one of the major factors contributing to the wage gap is the years lost in childcare by female employees. Also, some of them switch to part-time jobs, which are low paying compared to their previous employment in creating more time for their families. Thus to resolve this issue and reduce the burden on female employees, both parents need to participate in childcare. This way, female employees would raise children and, at the same time, develop their careers. In implementing this change, there is a need for the issuance of paternity leaves to fathers. On the same note, some female employees fail to access credible and reliable daycare services for their children and have to rely on their relatives and baby sitters. In addressing this problem, companies should set aside daycare centres that would care for the female employees’ children. The companies could arrange for the operation costs of these facilities to be deducted from the female employees’ salaries. The government should mandate this initiative through legislation. In the event of maternity leave, the government should incentivize employers to send off female workers during this period.

Professions Inclusion

The gender pay gap should be addressed through the inclusion of more women in the technology and science-based professions. From the analysis, one of the factors contributing to the gender pay gap is the exclusion of female workers from specific high paying sectors. This prejudice is a result of gender constructs and societal prototypes, whereby men are seen ideal for certain professions, whereas women are stereotyped against joining certain fields (Fortin and Böhm, 2017, p. 116). So far, there isn’t scientific evidence suggesting that certain genders are fit for specific careers. Hence, locking out women from these professions denies them the privilege of tapping the best talent. Therefore, there is a need for reforms in the career entry of the engineering and science fields. Hence, the admission should be based on merit and academic performance rather than gender constructs. Also, some female workers may be locked out of these jobs despite academic qualifications. The government should be stringent in the implementation of anti-discriminatory laws in the country.

Unequal pay could be resolved by including more women in management positions, seeing that the top management positions in most organizations are dominated by men. In some organizations, the wage rate between female and male workers is similar. Still, then discrepancies are uncovered upon analysis due to the recruiting of more male than female workers in leadership positions resulting in wage disparities (Atterton et al., 2019, p. 20). Part of the reason is the notion that men make better leaders, and they are better at disaster management and decision making. These misinformed perceptions result in more men than women qualifying for these positions. As a result, men receive more promotion opportunities and hence more salaries than their female counterparts. This is done by strategically placing the male workers in strategic departments that expose them to promotion opportunities. For instance, Walmart employees complained that the organization contracted more men in departments, which exposed them to promotional opportunities, as opposed to women. Therefore, in addressing the unequal pay gap, equal opportunities should be offered to both the male and female workforce

References

Apergis, N., Hayat, T. and Kadasah, N.A., 2019. Monetary policy and the gender pay gap: evidence from UK households. Applied Economics Letters, 26(21), pp.1807-1810.

Atterton, J., Meador, E., Markantoni, M., Thomson, S. and Jones, S., 2019. Exploring the Gender Pay Gap in Rural Scotland.

Brynin, M., 2017. The gender pay gap. Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report, (109).

Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R. and Parodi, F., 2018. The gender pay gap in the UK: children and experience in work (No. W18/02). IFS Working Papers..

Fortin, N.M., Bell, B. and Böhm, M., 2017. Top earnings inequality and the gender pay gap: Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Labour Economics, 47, pp.107-123.

Friedman, S. and Laurison, D., 2017. Mind the gap: financial L ondon and the regional class pay gap. The British journal of sociology, 68(3), pp.474-511.

Jones, M., Makepeace, G. and Wass, V., 2018. The UK gender pay gap 1997–2015: What is the role of the public sector?. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 57(2), pp.296-319.

Kentish, B., 2018. BBC Gender Pay Gap: 170 Female Employees Demand Apology over Salary Differences and ‘Culture of Discrimination’. The Independent.

Lips, H. M. 2013. The gender pay gap: Challenging the rationalizations. Perceived equity, discrimination, and the limits of human capital models. Sex Roles, 68(3-4), 169-185.

O’Neill, S., 2019. Gender pay gap grows. New Scientist, 241(3223), p.45.

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

write a report on the gender pay gap and also give some current situations with some example

A Critical Review of the Gender Pay Gap in the UK