Outcome Measures, Issues, and Opportunities

Organizational Functions, Processes, and Behaviors in High-Performing Healthcare Organizations or Practice Settings

High-performing hospitals are those that continuously attain excellence across several performance measures and in multiple departments. Hospital performance assessment has become a major factor among many health systems in countries of high income and increasingly so in countries of low- and middle-income levels (Groene, Skau, & Frølich, 2008; Braithwaite, Matsuyama & Johnson, 2017). Over the years, the data utilized from these assessments have become an indicator often used in hospital performance substantive variation, both in terms of evidence-based process adherence to care measures and care outcomes, which are also risk-adjusted (Runciman et al., 2012). High-performing healthcare facilities foster a supportive community, create operational alignment, reinforce accountability, increase engagement, and sift through the clutter. These organizations relentlessly pursue excellence and utilize technical proficiency in the context of teams. Additionally, these organizations use communication tools that aim at helping staff in the management of aggressive cost-reduction programs and organizational improvement. The communication carried out in high-performing organizations is high-value, more personal, transparent, and sensitive to staff concerns. Leadership ensures the messages on change are well understood, and the need for change is clear to all. Leaders view their employees as the greatest company assets and believe that when they take care of employees, then the employees will take even better care of patients.

According to Ahluwalia et al. (2017), senior leaders in high-performing organizations take time to assess a change model before adopting the same for utilization in the organization. The change model aids in aligning the vision, building acceptance, and holding employees accountable. In addition, leadership in these organizations ensures that the major initiatives have resources and a leadership plan that manages the process of change to ensure that the change is successful through the sustaining of unprecedented results. Further, high-performing organizations view data as one of their strategic assets and, with that, have analytic strategies that allow for data leveraging and actionable information to gain a market position that is both strategic and included in the organization’s value-based payer strategies. When successfully addressing the actionable information, these organizations can, for example, improve care access across strategic networks and healthcare networks; guide the change pace by moving to a fee-for-value from fee-for-service in supporting health initiatives through the creation of information architecture; decrease spending through continuous improvement of the provider network performance; evaluation of the clinical programs’ effectiveness and understanding the impact of the interventions while focusing on ROI; reducing patient out-migration and understanding referral patterns across the service delivery network for better management of care costs.

How Organizational Functions, Processes, and Behaviors Affect Outcome Measures Associated with the Identified Systemic Problem

High-performing organizations focus on safe and reliable performance through the embedding of core characteristics into the organization’s fabric. Leaders do this by building expectations into the daily strategies, routines, and roles of an organization. The expectations create predictability and order around practices and processes, thus allowing members of the organization to handle, with mindfulness, unexpected events. Unlike situational awareness, mindfulness provides organizations with a big perspective and helps identify early warning signs that require action. Mindfulness increases readiness and alertness to potential problems in the present time. The principles governing the leadership in this kind of organization encourage a timely response to unexpected events. When or if the event occurs, the staff members are psychologically ready to minimize disruption by working on recovery from the event (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2011). Additionally, these organizations emphasize the significance of predictable behaviors and routines. Thus, in fall prevention, fall risk assessments, fall risk reassessments, and routine interventions are incorporated into standard practice. A patient’s post-fall is quickly assessed to effect immediate intervention change or treatment while averting a reoccurrence.

Riley (2009) described four design and implementation tools for high reliability: healthcare bundles, a model of improvement, control charts, and process maps. All the tools can be applied in the prevention program of falls and injuries. Process maps are used to describe the assessment and reassessment of falls as well as the interventions and evaluations. They are also used in tracking intervention implementation timelines, from the generation of ideas to implementation and finally to the evaluation stage. Control charts may be used to analyze overall fall rates, fall types, repeat falls, severity level and injury, the time period between falls, and serious injury within the defined lower and upper control limits over time to determine the stability of the process. Several models on improvement are found in the literature and support fall reduction rates through improving the processes. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement or Plan-Do-Study-Act model is the most common one (Langley et al., 2009). Lastly, a fall bundle of interventions can be used based on the setting, population, and risk.

Quality and Safety Outcomes and Associated Measures

According to Morse (2008), inpatient falls can be categorized as accidental, anticipated, and unanticipated. These three categories will be assessed for changes, specifically, a decline in rates after the video monitoring process is implemented. By using these three categories, Morse asserts that approximately 78% of falls that are linked to anticipated physiologic events can be identified at an early stage and allow for safety measures to be put in place for fall prevention. Early identification of unexpected intrinsic events’ precursors and anticipated physiological fall identification can be predicted by screening patients, which could consequently prevent any falls.

Injuries related to falls in long-term care, home care, and community are characterized by the ANA-NDNQI fall-related categories of injuries as thus: none- where the patient sustained no injury from a fall; minor-where injuries require a minor intervention; moderate-where splints or sutures are administered; major-where injuries require further examination, casting, and surgery such as neurological injury; and death-resulting from sustained injuries.

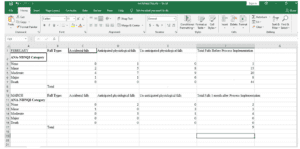

The fall incidences for March will be compared against those of February. These months are subject to change depending on when the project commences; the idea is to compare the rates prior to and after the implementation of the process. The different types of falls will be recorded against the three categories. The worksheet is shown in Appendix 1.

Performance Issues or Opportunities

Performance opportunities that may be identified in this process are based mainly on having a Sustainability Team. Once the process is successful, it will also be replicated in other departments. For this to be realized, a Sustainability Team will need to be put in place. Sustaining the efforts of the video monitoring process will call for responsibility to be clearly assigned. The Sustainability Team will take up the role of being the main dissemination point for new information, such as team education sessions with expert speakers on the topic of discussion, and will also take up new challenges, such as revising online documentation forms. The Sustainability Team will also be responsible for collecting data and regularly reporting on fall rate occurrences, which will be integrated fully into routine work processes. Regular meetings will also need to be held in which outcomes will be discussed and which will allow for policies and materials to be updated continuously.

One of the elements of keeping the Sustainability Team active is allowing team activities of different levels. A core group will meet once a month for data reviewing, while other team members will attend meetings on a need-basis. By so doing, persons will take part in the meetings and activities in a way that respects their time and also aid in maintaining a positive dynamic during the said meetings.

Measurement will be necessary if the improvement is to be achieved and more so to ensure that the program does not lose track. Measurement will also indicate if there is any success in the process, an aspect that is of particular interest to the leadership. For the regular measurement of fall rates, a routine workflow will need to be set up to collect data. The Sustainability Team members will have a person(s) who will calculate the fall rates from the incident reports and a person(s) who will be tasked with processes of fall-related care to ensure that occurrence is as expected. Additionally, the person(s) receiving the reports will need to be identified, and what will be done with the received data. For example, some areas will need to be defined, such as how soon the collected data needs to be sent for review before each Sustainability Team meeting. Integration of the Sustainability Team into the organization will ensure that the mission it sets out to do will continue.

Another performance opportunity lies in the Post Fall Huddles (PFH). The Joint Commission (2015) states that PFH is critical to an effective fall prevention program. Huddles will include all persons present when the fall occurred or involved in caring for the patient following a fall incident. The PFH will be carried out as soon as possible after a fall incident and should not occur after a shift’s end. Huddles have been shown to identify any fall trends and will do the same at the healthcare facility where this video monitoring program will be implemented. The PFH will also highlight the specific conditions that led to the fall and provide room for honest reporting, thus allowing for team transparency and better patient care (Ganz, Huang, Saliba & Shier, 2013). Team transparency and honest reporting will also be created via handoff reports, which include the fall risk of each patient and the appropriate interventions that are put in place (Quigley & White, 2013).

A Strategy for Ensuring That All Aspects of Patient Care Are Measured and That Knowledge Is Shared With the Staff

Once the pilot test is completed at the orthopedic ward, the information will be available on the areas that need education to enhance staff knowledge. Although this aspect is valuable, it is insufficient for changing practices. Staff members will also need to be assisted in figuring out how this new knowledge they acquire can be integrated into the existing practice and how the existing skills and practices may be less effective in comparison to other more effective skills and practices. Hence, several information-sharing methods for new practices are necessary. The adult learning theory opines that adults can learn best when the methods used are those that can be built into their individual experiences. Because people have diverse learning styles and are also at diverse practice proficiency levels, the educational approaches should be of different varieties. These educational approaches can be didactic methods which include different formats such as grand round talks, discussions, case study analyses, online lessons, interactive presentations, and lectures. Learning can also be enhanced by competency validation, care delivery observation by an expert practitioner, and simulations of care practice. Behavior changes can be gained from abstract knowledge through patient case reviews and clinical bedside reviews. All plans for change or new staff education should occur after close collaboration with the current fall prevention content experts. Learning will need ongoing support both as training for new staff and as refreshers for existing staff.

Lastly, the SAFE checklist will be implemented to ensure that universal fall precautions are complied with. Although not all the patients will be identified as high-risk fall patients, the SAFE checklist will be implemented on every patient, the risk assessment score notwithstanding. Every team member will be required to complete the SAFE checklist for every patient during every shift.

References

Ahluwalia, S. C., Damberg, C. L., Silverman, M., Motala, A., & Shekelle, P. G. (2017). What defines a high-performing health care delivery system: a systematic review. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(9), 450-459.

Braithwaite, J., Matsuyama, Y., & Johnson, J. (2017). Healthcare reform, quality and safety: perspectives, participants, partnerships and prospects in 30 countries. CRC Press.

Ganz, D.A., Huang C, Saliba, D. & Shier, V. (2013). Preventing falls in hospitals: A toolkit for improving quality of care. AHRQ Publication No. 13-0015-EF

Groene, O., Skau, J. K., & Frølich, A. (2008). An international review of projects on hospital performance assessment. International journal for quality in health care, 20(3), 162-171.

Islam, M. N., Furuoka, F., & Idris, A. (2020). Transformational leadership and employee championing behavior during organizational change: the mediating effect of work engagement. South Asian Journal of Business Studies.

Langley, G. J., Moen, R. D., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. John Wiley & Sons.

Quigley, P., White, S., (2013) Hospital-Based Fall Program Measurement and Improvement in High-Reliability Organizations. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 18 (2)

Riley, W. (2009). High reliability and implications for nursing leaders. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(2), 238-246.

Runciman, W. B., Hunt, T. D., Hannaford, N. A., Hibbert, P. D., Westbrook, J. I., Coiera, E. W., … & Braithwaite, J. (2012). CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia, 197(2), 100-105.

The Joint Commission, (2015). Sentinel Event Alert. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_55.pdf

Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2011). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty (Vol. 8). John Wiley & Sons.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Outcome Measures, Issues, and Opportunities

PART 3 of 4 part assignment

******************************

OVERVIEW:

Draft a 6-page report on outcome measures, issues, and opportunities for the executive leadership team or applicable stakeholder group.

Outcome Measures, Issues, and Opportunities

Note: Each assessment in this course builds on the work you completed in the previous assessment. Therefore, you must complete the assessments in this course in the order in which they are presented.

________________________

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

Organizational functions, processes, and behaviors can include leadership practices, communications, quality processes, financial management, safety and risk management, interprofessional collaboration, strategic planning, using the best available evidence, and questioning the status quo on all levels.

1. What are some examples of organizational functions, processes, and behaviors related to the outcome measures and performance issues discussed in your executive summary?

2. How would you implement change in addressing particular issues and opportunities?

3. In what ways do stakeholders support outcome success?

________________________

ASSIGNMENT INSTRUCTIONS:

This assessment is based on the executive summary you prepared in the previous assessment.

Preparation:

Your executive summary captured the attention and interest of the executive leadership team, who have asked you to provide them with a detailed report addressing outcome measures and performance issues or opportunities, including a strategy for ensuring that all aspects of patient care are measured.

Requirements:

The requirements outlined below correspond to the grading criteria in the Outcome Measures, Issues, and Opportunities Scoring Guide. Be sure that your written analysis addresses each point at a minimum. You may also want to read the Outcome Measures, Issues, and Opportunities Scoring Guide and Guiding Questions: Outcome Measures, Issues, and Opportunities (linked in the Resources) to better understand how each criterion will be assessed.

Drafting the Report:

1. Analyze organizational functions, processes, and behaviors in high-performing healthcare organizations or practice settings.

2. Determine how organizational functions, processes, and behaviors affect outcome measures associated with the systemic problem identified in your gap analysis.

3. Identify the quality and safety outcomes and associated measures relevant to the performance gap you intend to close. Create a spreadsheet showing the outcome measures.

4. Identify performance issues or opportunities associated with particular organizational functions, processes, and behaviors and the quality and safety outcomes they affect.

5. Outline a strategy using a selected change model to ensure that all aspects of patient care are measured and that knowledge is shared with the staff.

Writing and Supporting Evidence:

1. Write coherently and with purpose for a specific audience, using correct grammar and mechanics.

2. Integrate relevant and credible sources of evidence to support assertions, correctly formatting citations and references using APA style.

Additional Requirements

Format your document using APA style. ****7th Edition****

1. Use the APA paper template linked in the resources. Be sure to include:

A title page and reference page. An abstract is not required.

A running head on all pages.

Appropriate section headings.

Properly-formatted citations and references.

2. Your report should be 6 pages in length, not including the title page and reference page.

3. Add your Quality and Safety Outcomes spreadsheet to your report as an addendum.*****

________________________________________________________

Suggested Resources

The resources provided here are optional. You may use other resources of your choice to prepare for this assessment; however, you will need to ensure that they are appropriate, credible, and valid.

Outcomes Measures and Process Improvement:

The following resources provide context and background information that will help you with this assessment.

1. Fessele, K, Yendro, S., & Mallory, G. (2014). Setting the bar: Developing quality measures and education programs to define evidence-based, patient-centered, high-quality care. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 7–11.

– In this article, the authors discuss how one group developed and then tested relevant quality measures.

2. Goll, C. & Cahill, S. (2014). Leading the way: Enculturating the value of process improvement. American Nurse Today, 9(8), 1–4.

– In this article, the authors contend that the importance of a culture of accountability and ownership is crucial to attaining organizational outcomes.

3. Huffstutler, C.D. & Thomsen, D. (2015). A framework for performance excellence and success. Frontiers of Health Science Management, 32(1), 45–50.

– In this article, the authors present a framework that describes the behaviors and beliefs of high-performing organizations.

5. Masica, A. L., Richter, K. M., Convery, P., & Haydar, Z. (2009). Linking Joint Commission inpatient core measures and National Patient Safety Goals with evidence. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 22(2), 103–111.

– In this article, the authors summarize the relationships between Joint Commission core measures, safety goals, and patient outcomes.

6. The Joint Commission (n.d.). National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). Retrieved from http://nursingandndnqi.weebly.

– Explore this resource and examine the indicators related to the effects of nursing on safety, quality, and outcomes.

Change Theory:

1. Mitchell, G. (2013). Selecting the best theory to implement planned change. Nursing Management, 20(1), 32–37.

This article may help you in outlining a strategy for change.