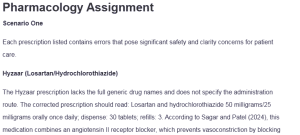

Pharmacology Assignment

Scenario One

Each prescription listed contains errors that pose significant safety and clarity concerns for patient care.

Hyzaar (Losartan/Hydrochlorothiazide)

The Hyzaar prescription lacks the full generic drug names and does not specify the administration route. The corrected prescription should read: Losartan and hydrochlorothiazide 50 milligrams/25 milligrams orally once daily; dispense: 30 tablets; refills: 3. According to Sagar and Patel (2024), this medication combines an angiotensin II receptor blocker, which prevents vasoconstriction by blocking angiotensin II, with a thiazide diuretic that increases urinary excretion of sodium and water to help lower blood pressure: Pharmacology Assignment.

Lotrel (Amlodipine/Benazepril)

The Lotrel order is inaccurate because it uses a nonstandard combination dose and omits the full generic drug names. A correct version of the order is: Amlodipine and benazepril 5 milligrams/40 milligrams orally once daily; dispense: 30 tablets; refills: 3. Amlodipine is under calcium channel blockers which reduce peripheral vascular resistance, while benazepril is classified as an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor that decreases blood pressure by interrupting the renin-angiotensin system.

Hydralazine

The drug name in this prescription is misspelled, and the administration frequency is not expressed using standard medical terminology. The corrected version is: Hydralazine 25 milligrams orally four times daily; dispense: 120 tablets; refills: 1. Hydralazine is a direct-acting vasodilator that acts primarily on arteriolar smooth muscle to reduce systemic vascular resistance and lower blood pressure. Proper spelling, frequency, and formatting ensure safe prescribing and pharmacist interpretation.

Digoxin

The dosage of digoxin in the original prescription is exceedingly high and potentially dangerous for most patients. A safer and commonly prescribed maintenance dose is Digoxin 0.125 milligrams orally once daily; dispense: 30 tablets; refills: 1. Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside that improves cardiac output by blocking the sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase pump, thereby increasing intracellular calcium concentration in the myocardium (David & Shetty, 2024). Using clinically accepted doses minimizes the risk of toxicity and adverse cardiac effects.

Repatha (Evolocumab)

The Repatha prescription contains a route of administration error, as it is incorrectly listed as intravenous. The correct prescription should be: Evolocumab 140 milligrams subcutaneously every two weeks; dispense: 2 prefilled syringes; refills: 1. According to Lamia et al. (2024), Evolocumab is a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor that enhances the ability of the liver to clear low-density lipoprotein cholesterol from the bloodstream.

Scenario Two

First-Pass Effect and Bioavailability

Fentanyl has a high first-pass effect when administered per oral, resulting in extensive hepatic metabolism before it can reach systemic circulation. This lowers its bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy (Herman & Santos, 2023). Therefore, oral administration is not a clinically useful route for fentanyl, and alternative administration methods are necessary to bypass liver metabolism.

Route with 100 percent Bioavailability.

The intravenous route provides a hundred percent bioavailability, making it the most direct and reliable method for achieving therapeutic blood concentrations of fentanyl. This route bypasses gastrointestinal and hepatic first-pass metabolism, allowing the full dose to enter systemic circulation (Kim & De Jesus, 2023). In emergency or acute care settings, intravenous administration is preferred for rapid onset of analgesia.

Alternative Routes

To bypass the first-pass effect, fentanyl can be administered as transdermal patches, buccal tablets, or sublingual sprays (Ramos-Matos et al., 2023). These routes allow the drug to be absorbed into the systemic circulation directly through the skin or mucous membranes. Such formulations are especially useful in chronic pain management or for patients requiring steady plasma concentrations.

Sample Prescription for Fentanyl

A valid prescription to avoid first-pass metabolism would be: Fentanyl citrate buccal tablet 100 micrograms; place one tablet in the buccal cavity every two hours as needed for severe pain; dispense: 30 tablets; refills: none. This route ensures rapid absorption and effective analgesia in opioid-tolerant patients. Caution should be taken to assess opioid tolerance, and concurrent sedating medications should be reviewed.

Scenario Three

Cytochrome P450 Enzymes Location

The majority of cytochrome P450 enzymes are found in the liver, and they are essential for the phase one metabolism of many medications (Gilani & Cassagnol, 2023). These enzymes catalyze oxidation reactions that increase the water solubility of drugs, facilitating their elimination. Knowledge of their activity is crucial for predicting drug interactions and individualized dosing.

Identification of the Medication

Using the Medscape Pill Identifier with the imprint 292, oval shape, brown color, and tablet form, the medication was identified as oxycodone hydrochloride 5 milligrams. Oxycodone is a semi-synthetic opioid analgesic used for the treatment of moderate to severe pain (Sadiq et al., 2024). To prevent errors, it is essential to verify pill identification before initiating or continuing therapy.

Primary Cytochrome Enzyme Involved

Oxycodone is mainly metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 and, to a lesser extent, by cytochrome P450 2D6. Inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4, for instance, ketoconazole, can significantly increase serum oxycodone levels, increasing the risk of respiratory depression (Sadiq et al., 2024). Cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers, such as rifampin, may reduce therapeutic efficacy by increasing clearance.

Application to Medication Therapy Management

Understanding the cytochrome pathway involved in oxycodone metabolism allows healthcare providers to anticipate drug interactions and adjust doses accordingly. Medication therapy management should include reviewing the patient’s current medications for enzyme inhibitors or inducers. This helps prevent toxic effects or subtherapeutic dosing, especially in elderly or polymedicated patients.

Sample Prescription for Oxycodone

A complete and appropriate prescription would be: Oxycodone hydrochloride 5 milligrams orally every four to six hours as needed for moderate to severe pain; dispense: 60 tablets; refills: none. This should be prescribed with careful monitoring of sedation level, respiratory rate, and effectiveness of pain control (Preuss et al., 2023). Patients should be counseled on the risks of concurrent alcohol or sedative use.

Scenario Four

Interpretation of Lipid Profile

DL’s lipid panel reveals total cholesterol of 245 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 41 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 165 mg/dL, and triglycerides of 175 mg/dL. These levels exceed the recommended targets, which are total cholesterol less than 200 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein greater than 40 mg/dL for men, low-density lipoprotein less than 100 mg/dL, and triglycerides less than mg/dL. According to Huff et al. (2023), the high level of low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol indicate a need for pharmacologic therapy and lifestyle changes.

Recommended Treatment Plan

According to the current American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines, DL should be initiated on a high-intensity statin (Sizar et al., 2024). The red yeast rice supplement should be discontinued due to variability in potency and the potential for adverse hepatic effects. Additional lifestyle counseling should include smoking cessation, dietary modification, weight loss, and increased physical activity.

Complete Medication Order for Statin Therapy

The appropriate medication order is: Atorvastatin 40 milligrams orally once daily at bedtime; dispense: 30 tablets; refills: 3. According to McIver and Siddique (2020), Atorvastatin is a hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor that lowers cholesterol synthesis in the liver and accelerates low-density lipoprotein clearance from the bloodstream. This statin is effective in achieving significant reductions in low-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol levels.

Obesity Classification

At 5 feet 10 inches tall and 223 pounds, DL’s body mass index is 32.0 kilograms per square meter using the Medscape body mass index calculator. This puts him in the obese class, further compounding his risk of cardiovascular disease (Zierle-Ghosh & Jan 2023). Addressing his weight through diet, exercise, and pharmacologic support will improve lipid control and reduce cardiovascular morbidity.

Patient Education and Monitoring

DL should be educated on the importance of adherence to statin therapy and potential side effects, including myopathy and liver enzyme elevation. Liver function tests and a fasting lipid panel should be reassessed in 4 to 12 weeks to evaluate efficacy and safety. Ongoing lifestyle support and periodic monitoring will help optimize cardiovascular outcomes and promote long-term health.

Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors

DL presents with at least four established risk factors for coronary artery disease: active tobacco use, elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hypertension as suggested by losartan use, and obesity. Synergistically, these factors increase the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases (Nakamura et al., 2020). A multifaceted approach addressing pharmacologic and lifestyle interventions is essential to reduce his overall risk profile.

References

David, M. N. V., & Shetty, M. (2024, November 25). Digoxin. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556025/

Gilani, B., & Cassagnol, M. (2023, April 24). Biochemistry, cytochrome P450. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557698/

Herman, T. F., & Santos, C. (2023, November 3). First Pass Effect. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551679/

Huff, T., Boyd, B., & Jialal, I. (2023, March 6). Physiology, Cholesterol. National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470561/

Kim, J., & De Jesus, O. (2023, August 23). Medication routes of administration. National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568677/

Lamia, T. H., Shah-Riar, P., Khanam, M., Khair, F., Sadat, A., Maksuda Khan Tania, Haque, S. M., Saaki, S. S., Aysha Ferdausi, Sadia Afrin Naurin, Tabassum, M., Riffat E Tasnim Rahie, & Hasan, R. (2024). Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (PCSK9) Inhibitors as Adjunct Therapy to Statins: A New Frontier in Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.71365

McIver, L. A., & Siddique, M. S. (2020, September 25). Atorvastatin. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430779/

Nakamura, M., Yamamoto, Y., Imaoka, W., Kuroshima, T., Toragai, R., Ito, Y., Kanda, E., Schaefer, E. J., & Ai, M. (2020). Relationships between Smoking Status, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and Lipoproteins in a Large Japanese Population. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis, advpub(9). https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.56838

Preuss, C. V., Kalava, A., & King, K. C. (2023, April 29). Prescription of Controlled Substances: Benefits and Risks. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537318/

Ramos-Matos, C. F., Lopez-Ojeda, W., & Bistas, K. G. (2023). Fentanyl. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459275/

Sadiq, N. M., Dice, T. J., & Mead, T. (2024). Oxycodone. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482226/

Sagar, S., & Patel, P. (2024, August 16). Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and HCTZ Combination Drugs. Nih.gov; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606100/

Sizar, O., Khare, S., Jamil, R. T., & Talati, R. (2024, February 29). Statin Medications. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430940/

Zierle-Ghosh, A., & Jan, A. (2023). Physiology, body mass index (BMI). National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535456/

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Pharmacology

To Prepare:

- Review the case study posted in “Announcements” by your Instructor for this Assignment

- Review the information provided and answer questions posed in the case study

- When recommending a medication, write out a complete prescription for the medication

- Whenever possible, use clinical practice guidelines in developing your answers when possible

- Include at least three references to support your answer and cite them in APA format.

DIRECTIONS:

For each of the scenarios below, answer the questions using your learning resources, Medscape, and clinical practice guidelines (ie JNC 8, AHA, ACC, etc). Lecturio is an optional resource but highly recommended. Be sure to thoroughly answer ALL questions. When recommending medications, write out a complete medication order. What would you send to a pharmacy?

Include drug, dose, route, frequency, special instructions, # dispensed (days supply,) and refill information. Also state if you would continue, discontinue or taper the patient’s current medications. Review and discuss ALL labs and possible interactions.

Pharmacology Assignment

Use at least 3 sources for each scenario and cite sources using APA format; include in-text citations. You do not need an introduction or conclusion paragraph. Please also review the assignment rubric.

Resources

- Rosenthal, L. D., & Burchum, J. R. (2021). Lehne’s pharmacotherapeutics for advanced practice nurses and physician assistants (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

- Chapter 37, “Diuretics” (pp. 290–296)

- Chapter 38, “Drugs Acting on the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System” (pp. 297–307)

- Chapter 39, “Calcium Channel Blockers” (pp. 308–312)

- Chapter 40, “Vasodilators” (pp. 313–315)

- Chapter 41, “Drugs for Hypertension” (pp. 316–324)

- Chapter 42, “Drugs for Heart Failure” (pp. 325–336)

- Chapter 43, “Antidysrhythmic Drugs” (pp. 337–348)

- Chapter 44, “Prophylaxis of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease” (pp. 349–363)

- Chapter 45, “Drugs for Angina Pectoris” (pp. 364–371)

- Chapter 46, “Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Drugs” (pp. 372–388)