Evidence-Based Project – Implementing CBT for Adolescent Depression

Hello. The topic for today’s presentation is an evidence-based practice change to help improve treatment outcomes for adolescents with depression. More specifically, I will be discussing the implementation of a formal cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, protocol at our community mental health center.

This project was initiated in reaction to observed clinical challenges—namely, the partial effectiveness of current treatment modalities in fully alleviating depressive symptoms in a significant proportion of adolescent patients. Through an extensive review and critical analysis of available literature, I identified CBT as an evidence-based treatment that, when delivered systematically, has the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes.

Throughout this presentation, I will walk you through the organizational context, the problem we are addressing, the evidence base for CBT, our proposed implementation plan, timeline, evaluation measures, and expected outcomes. The goal is not only to enhance the quality of care we provide but also to allow adolescent patients to have the best possible opportunity at full recovery. Welcome.

Our community mental health center serves a heterogeneous population of adolescents aged 12-18 with various mental health problems in urban and suburban communities. There is a robust organizational culture of evidence-based practice with leadership that consistently encourages innovation and improvement in practice. This support is conducive to an environment prepared for the implementation of change. The personnel are a multidisciplinary team of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses who collaborate in the delivery of mental health services. We possess a robust electronic health record system with the ability to accommodate new treatment protocols and outcome measures. The center holds regular staff meetings, monthly case conferences, and quarterly staff training on clinical skill development and implementation of best practices. Organizational climate surveys done recently indicate high staff engagement and openness to quality improvement activities, which is a good indication of readiness to implement new evidence-based practices in adolescent depression treatment.

While using varying treatment methods for depression among adolescents, our center has realized many patients who arrive with partial remission of symptoms. According to Cuijpers et al. (2023), depression affects 10-20% of adolescents across the globe, thereby making it a significant clinical problem with potential long-term consequences. Our internal quality measures over the past 18 months indicate that approximately 45% of depressed adolescents remain above clinical cutoffs following completion of standard treatment, a finding that is consistent with those of Stikkelbroek et al. (2020), where 41.6% remained above clinical cutoffs at post-treatment. Chart audit demonstrates uneven application of evidence-based protocol with non-systematic use of core CBT components. This offers a great opportunity to consolidate our depression treatment modality and optimize outcomes. Key stakeholders include adolescent patients and their families who lodge complaints about incomplete recovery, clinical practitioners who prefer more effective interventions, and administrators who are concerned with quality measures and resource utilization. Closing this gap would make a considerable difference in clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Based on a critical appraisal of four high-quality studies, I recommend implementing complete CBT protocols with flexible component sequencing for adolescent depression treatment. Cuijpers et al.’s (2023) comprehensive meta-analysis of 409 trials with 52,702 patients showed moderate effects specifically for adolescents (g=0.41), providing Level I evidence supporting CBT as a first-line treatment. Van Den Heuvel et al. (2021) demonstrated that while complete protocols incorporating all components are necessary for optimal outcomes, the sequence of delivering cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, problem-solving, and relaxation can be flexible without compromising effectiveness. Walter et al. (2021) highlighted CBT effectiveness in routine practice settings with large effect sizes (d=0.85-1.30) for clinical patients, though noting that extended treatment duration may be necessary for full symptom remission. Systematic outcome monitoring is essential for identifying poor responders early, enabling timely implementation of augmentation strategies. Standardized documentation will facilitate quality assurance and continuous improvement while allowing flexible clinical decision-making within the evidence-based framework.

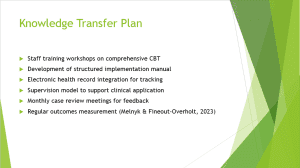

Knowledge transfer will occur through multiple complementary channels to ensure successful implementation. We will conduct a series of comprehensive staff training workshops led by certified CBT experts, focusing on the practical application of all protocol components. These workshops will include didactic instruction, demonstration, role-playing, and case application exercises. We’ll develop a structured implementation manual with decision-making algorithms and flexible component sequencing options based on patient presentation. Integration with our electronic health record will facilitate standardized documentation, fidelity monitoring, and outcome tracking through built-in templates and assessment measures. A supervision model with experienced CBT practitioners will provide ongoing support for clinicians implementing the protocols, with weekly group supervision initially transitioning to biweekly as competence increases. Monthly case review meetings will create opportunities for problem-solving and protocol refinement. Regular outcomes measurement using validated instruments will establish a continuous improvement cycle, aligning with Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt’s (2023) recommendations for sustainable evidence-based practice implementation in clinical settings.

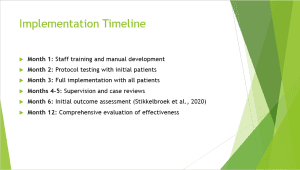

The implementation will follow a structured timeline to ensure appropriate preparation, gradual adoption, and ongoing support. Month 1 focuses intensively on staff training through four half-day workshops and concurrent development of the implementation manual with staff input to increase ownership. Month 2 involves initial testing with a subset of 10-15 patients to identify and address implementation challenges before a broader rollout. Full implementation begins in Month 3 with all eligible adolescent patients with depression. Months 4-5 emphasize weekly supervision sessions and biweekly case reviews to support protocol fidelity, address emerging challenges, and make necessary adjustments. Initial outcome assessment occurs at Month 6, aligning with research by Stikkelbroek et al. (2020) showing significant improvements at six-month follow-up. This assessment will examine both process measures (like protocol adherence and documentation quality) and outcome measures (like symptom reduction and remission rates). A comprehensive evaluation at Month 12 will analyze full-year data to determine overall effectiveness, identify subgroups with differential responses, and inform potential protocol refinements for sustainable implementation.

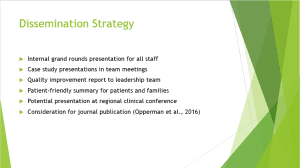

Results will be disseminated through multiple channels to reach all relevant stakeholders effectively. We will conduct an internal grand round presentation for all clinical and support staff to share findings, implementation experiences, and outcomes. Regular case study presentations in team meetings will illustrate the practical application of the protocols and demonstrate real-world effectiveness. A comprehensive quality improvement report will inform the leadership team about implementation processes, challenges, solutions, and outcomes to support resource allocation decisions. We’ll develop patient-friendly summaries explaining the approach and outcomes for adolescents and families, enhancing transparency and engagement. If successful, we’ll consider presenting our implementation process and results at regional clinical conferences to benefit the broader mental health community. Following Opperman et al.’s (2016) model for evaluating professional development initiatives, we will document both process and outcome metrics with potential publication in implementation science or clinical practice journals. This multi-level dissemination strategy ensures information reaches all stakeholders in appropriate formats and potentially contributes to the broader knowledge base.

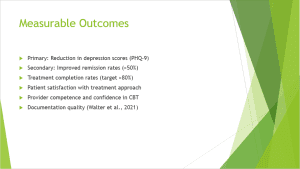

We will track several measurable outcomes to comprehensively evaluate implementation success and clinical impact. The primary outcome measure will be a reduction in PHQ-9 depression scores, with a target improvement of at least 50% from baseline and scores below the clinical threshold of 10. This aligns with validated measures used in our reference studies. Secondary outcomes include remission rates (aiming for >50% of patients below clinical threshold compared to the current 30%) and treatment completion rates (target >80% compared to the current 65%). Patient satisfaction will be assessed using standardized surveys administered at treatment midpoint and completion. Provider competence will be evaluated through structured supervision ratings and self-efficacy measures before and after implementation. Documentation quality will be assessed through structured chart audits examining adherence to protocol components, similar to the methodology in Walter et al.’s (2021) study. These metrics create a balanced scorecard approach to evaluating clinical outcomes, process quality, and stakeholder perspectives. Data will be analyzed quarterly to identify trends and opportunities for adjustment, with statistical comparison to the pre-implementation baseline.

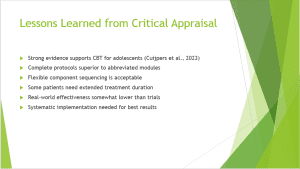

Critical analysis of the four studies provided valuable insight to inform our implementation strategy directly. Cuijpers et al. (2023) produced Level I evidence from their long meta-analysis over 409 trials, yielding solid evidence supporting CBT in the treatment of adolescent depression with effect sizes of g=0.41. Its solid evidence base supports CBT as our main intervention strategy. Van Den Heuvel et al. (2021) revealed that complete protocols with all components are required for optimal effectiveness, but the shortened three-session modules were not sufficient. Nevertheless, they also found that the order of delivery of the components can vary without affecting effectiveness and that personalization is facilitated. Stikkelbroek et al. (2020) highlighted that some patients require longer treatment, with continuous improvement at 6-month follow-up, suggesting longer treatment duration in some patients. Walter et al. (2021) demonstrated CBT efficacy in routine practice but suggested real-world results to be a little less than in randomized controlled trials, warning us of realistic expectations. Cumulatively, this information informed our implementation approach of whole protocols with flexible sequencing and duration supported by systematic outcome monitoring.

Cuijpers, P., Miguel, C., Harrer, M., Plessen, C. Y., Ciharova, M., Ebert, D., & Karyotaki, E. (2023). Cognitive behavior therapy vs. control conditions, other psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and combined treatment for depression: A comprehensive meta‐analysis including 409 trials with 52,702 patients. World Psychiatry, 22(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21069

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2023). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (5th ed.). LWW.

Opperman, E. A., Liebig, D., Bowling, J., Johnson, C., & Harper, D. C. (2016). Measuring return on investment for professional development activities in nursing. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 32(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000256

Stikkelbroek, Y., Bodden, D. H. M., Kleinjan, M., Reijnders, M., & van Baar, A. L. (2020). Adolescent depression and the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy: Outcomes at 12-month follow-up in a randomized controlled trial. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00332-9

Van Den Heuvel, M., Bodden, D. H. M., van Rossum, L., Muris, P., & Hogendoorn, S. M. (2021). Protocol integrity and clinical effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102038

Walter, H., Palm, C., Neumann, A., Steinhausen, H. C., & Schmidt, M. H. (2021). Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in routine care: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(4), 248–258.

ORDER A PLAGIARISM-FREE PAPER HERE

We’ll write everything from scratch

Question

Evidence-Based Project – Implementing CBT for Adolescent Depression

Evidence-Based Project, Part 4: Recommending an Evidence-Based Practice Change

The collection of evidence is an activity that occurs with an endgame in mind. For example, law enforcement professionals collect evidence to support a decision to charge those accused of criminal activity. Similarly, evidence-based healthcare practitioners collect evidence to support decisions in pursuit of specific healthcare outcomes.

Evidence-Based Project – Implementing CBT for Adolescent Depression

In this Assignment, you will identify an issue or opportunity for change within your healthcare organization and propose an idea for a change in practice supported by an EBP approach.

Required Reading

- Hoffman, T. C., Montori, V. M., & Del Mar, C. (2014). The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision makingLinks to an external site.. Journal of the American Medical Association, 312(13), 1295–1296. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10186

- Kon, A. A., Davidson, J. E., Morrison, W., Danis, M., & White, D. B. (2016). Shared decision making in intensive care units: An American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society policy statementLinks to an external site.. Critical Care Medicine, 44(1), 188–201. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001396

- Opperman, C., Liebig, D., Bowling, J., & Johnson, C. S., & Harper, M. (2016). Measuring return on investment for professional development activities: Implications for practiceLinks to an external site.. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 32(4), 176–184. doi:10.1097/NND.0000000000000483

- Schroy, P. C., Mylvaganam, S., & Davidson, P. (2014). Provider perspectives on the utility of a colorectal cancer screening decision aid for facilitating shared decision makingLinks to an external site.. Health Expectations, 17(1), 27–35. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00730.xThe Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. (2019). Patient decision aidsLinks to an external site.. Retrieved from https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/

To Prepare:

- Reflect on the four peer-reviewed articles you critically appraised in Module 4, related to your clinical topic of interest and PICOT.

- Reflect on your current healthcare organization and think about potential opportunities for evidence-based change, using your topic of interest and PICOT as the basis for your reflection.

- Consider the best method of disseminating the results of your presentation to an audience.

The Assignment: (Evidence-Based Project)

Part 4: Recommending an Evidence-Based Practice Change

Create an 8- to 9-slide narrated PowerPoint presentation in which you do the following:

- Briefly describe your healthcare organization, including its culture and readiness for change. (You may opt to keep various elements of this anonymous, such as your company name.)

- Describe the current problem or opportunity for change. Include in this description the circumstances surrounding the need for change, the scope of the issue, the stakeholders involved, and the risks associated with change implementation in general.

- Propose an evidence-based idea for a change in practice using an EBP approach to decision making. Note that you may find further research needs to be conducted if sufficient evidence is not discovered.

- Describe your plan for knowledge transfer of this change, including knowledge creation, dissemination, and organizational adoption and implementation.

- Explain how you would disseminate the results of your project to an audience. Provide a rationale for why you selected this dissemination strategy.

- Describe the measurable outcomes you hope to achieve with the implementation of this evidence-based change.

- Be sure to provide APA citations of the supporting evidence-based peer reviewed articles you selected to support your thinking.

- Add a lessons learned section that includes the following:

- A summary of the critical appraisal of the peer-reviewed articles you previously submitted

- An explanation about what you learned from completing the Evaluation Table within the Critical Appraisal Tool Worksheet Template (1-3 slides)

Alternate Submission Method

You may also use Kaltura Personal Capture to record your narrated PowerPoint. This option will require you to create your PowerPoint slides first. Then, follow the Personal Capture instructions outlined on the Kaltura Media Uploader guideLinks to an external site.. This guide will walk you through downloading the tool and help you become familiar with the features of Personal Capture. When you are ready to begin recording, you may turn off the webcam option so that only “Screen” and “Audio” are enabled. Start your recording and then open your PowerPoint to slide show view. Once the recording is complete, follow the instructions found on the “Posting Your Video in the Classroom Guide” found on the Kaltura Media Uploader page for instructions on how to submit your video. For this option, in addition to submitting your video, you must also upload your PowerPoint file which must include your speaker notes.